OECD Report About Climate Finance (The Hindu)

- 22 Nov 2023

Why is it in the News?

A new report, published by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), showed that economically developed countries fell short of their promise to jointly mobilise $100 billion a year, towards the climate mitigation and adaptation needs of developing countries, in 2021 – one year past the 2020 deadline.

What is the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)?

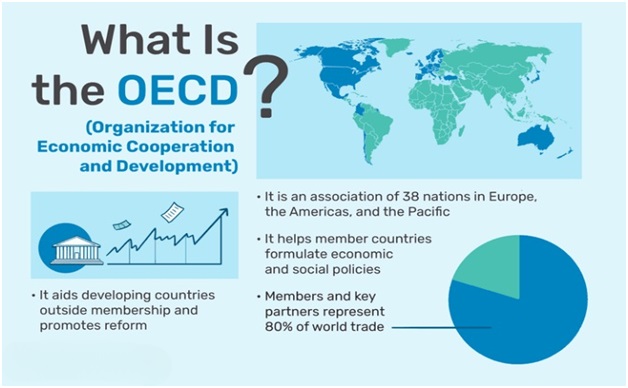

- The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is an association of 38 nations in Europe, the Americas, and the Pacific.

- Its members and key partners represent 80% of world trade and investment.

- The goal of the OECD is to promote the economic welfare of its members.

- It also coordinates its efforts to aid developing countries outside of its membership.

- As a result, its programs help promote reform in more than 100 countries worldwide.

- The OECD's main headquarters is located in Paris (France)

- The OECD collects, analyzes, and reports on economic growth data for its members.

- This gives them the knowledge to further their prosperity and fight poverty. It also balances the impact of economic growth on the environment.

- Committees within the OECD analyze the data and make policy recommendations.

- It's up to each member country to decide how to use OECD recommendations.

- The OECD publishes mainly two reports:

- International Migration Outlook

- Programme for International Student Assessment

Key Findings of the OECD Report Ahead of COP 28:

- The OECD has released a report titled 'Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013-2021.'

- This comprehensive report highlights the collective patterns in annual climate finance contributed and mobilized by developed nations for developing countries during the period from 2013 to 2021.

- In-depth analyses are presented, offering insights into climate themes, sectors, financial instruments, and regional distributions specifically for the years 2016 to 2021.

- Additionally, the report offers essential recommendations for international providers to enhance financial support for adaptation efforts and to more efficiently engage private finance in climate action.

Major Takeaways from the Report Published by OECD:

- Failure to Meet Commitments: The report revealed that the economically developed countries had failed to meet their commitment to together raise $100 billion annually by 2021, one year after the 2020 deadline, to help developing nations with their climate adaptation and mitigation needs.

- According to the report, affluent nations raised $89.6 billion in 2021, however, the amount of money allocated for adaptation decreased by 14% from 2020 to 2021.

- The ability of developing nations to meet their needs for climate adaptation and mitigation is lowered when sufficient climate funding is not raised.

- It also weakens confidence in the industrialized world's sincerity in addressing the climate catastrophe among the world's poorer nations.

- Loan-Centric Climate Finance: According to the OECD study, $49.6 billion in loans were given out of the $73.1 billion that the public sector raised in 2021 through bilateral and multilateral channels.

- It illuminates the degree to which wealthy nations must rely on loans at market rates in order to meet their climate finance commitments.

- For instance, a research team's evaluation of the worldwide flows of climate finance from 2011 to 2020 revealed that 61% of the funding came from loans.

Issue With 'Additionality'

- Another issue in the OECD report pertains to additionality.

- The UNFCCC states that developed countries “shall provide new and additional financial resources to meet the agreed full costs incurred by developing country Parties in complying with their obligations under the convention”.

- This means developed countries can’t cut overseas development assistance (ODA) in order to finance climate needs because that would effectively rob Peter to pay Paul.

- In the real world, it could cut off support for healthcare in order to reallocate that money to, say, install solar panels.

- The “new and additional finance” also means developed countries can’t double-count.

- For example, a renewable energy project could contribute to both emission reductions and overall development in a region.

- As per the U.N. Convention, however, donor countries can’t categorise such funding as both ODA and climate finance because it wouldn’t fulfill the “new and additional” criterion.

- A few years ago, European Union officials admitted to double-counting development aid as climate finance.

What Counts as Climate Finance?

- At present, there is no commonly agreed definition of ‘climate finance’ because developed countries have endeavored repeatedly to keep it vague.

- For example, at the COP 27 in Egypt last year, Australia and the U.K. even sought to end discussions to define ‘climate finance’.

- In the run-up to the COP 26 in Glasgow, the U.S. led an effort to block debate on a common definition, alongside Switzerland, Sweden, and some other developed countries.

- The lack of definitional clarity has reportedly led to strange situations like funding for chocolate and gelato stores in Asia and a coastal hotel expansion in Haiti being tagged as climate finance.

- The ambiguity works in favour of richer countries because it leaves the door open to arbitrarily classify any funding, including ODA and high-cost loans, as climate finance and escape the scrutiny that a clearer definition might bring.

- So while developed countries can claim they have provided billions in climate finance, the actual flows need to be checked for whether they actually went into climate mitigation and adaptation in developing countries or something else.

How much do developing countries need?

- According to the OECD assessment, climate investments for developing nations are expected to reach approximately $1 trillion year by 2025 and $2.4 trillion annually between 2026 and 2030.

- In contrast, the $100 billion objective is insufficient and even more so given that it has not yet been reached.

What role can the private sector play?

- To meet the scale of the challenge, people like the U.S. climate envoy John Kerry and World Bank president Ajay Banga have routinely emphasised the role the private sector could play.

- But the OECD report shows that private financing for climate action has stagnated for a decade.

- The problem is particularly worse for climate adaptation because investment in this sector can’t generate the sort of high returns that private investors seek.

- There also haven’t yet been signs that the private sector is interested in massively scaling up its climate investments.

What is Climate Change?

- Climate change is the result of long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns.

- Natural variations, like those influenced by changes in the solar cycle, can contribute to these shifts.

- However, since the 1800s, human activities, particularly the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas, have emerged as the primary driver of climate change.

- The combustion of fossil fuels produces greenhouse gas emissions, creating a metaphorical blanket around the Earth.

- This 'blanket' traps the sun's heat, leading to an increase in temperatures.

- The rising temperatures, a consequence of climate change, accelerate the melting of ice.

- This, in turn, contributes to elevated sea levels, resulting in flooding and erosion.