Global Hunger Index 2024

- 17 Oct 2024

Why in the news?

India is ranked 105th among 127 countries in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2024, indicating a ‘serious’ level of hunger, along with Afghanistan and Pakistan, which also face hunger challenges.

According to the Global Hunger Index released on 10th October 2024, the hunger levels in 42 countries are at alarming levels, making the goal of Zero Hunger by 2030 unattainable. At this pace of progress, the world will not even attain a low hunger level until 2160. The world’s GHI score is 18.3, which is considered moderate in the severity of hunger scale.

Key Takeaways:

1. The GHI is published by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe annually to measure and track hunger at global, regional, and national levels. The purpose of the report is to create awareness and understanding of the struggle against hunger and call attention to those areas of the world where hunger levels are highest and there is a need for additional efforts.

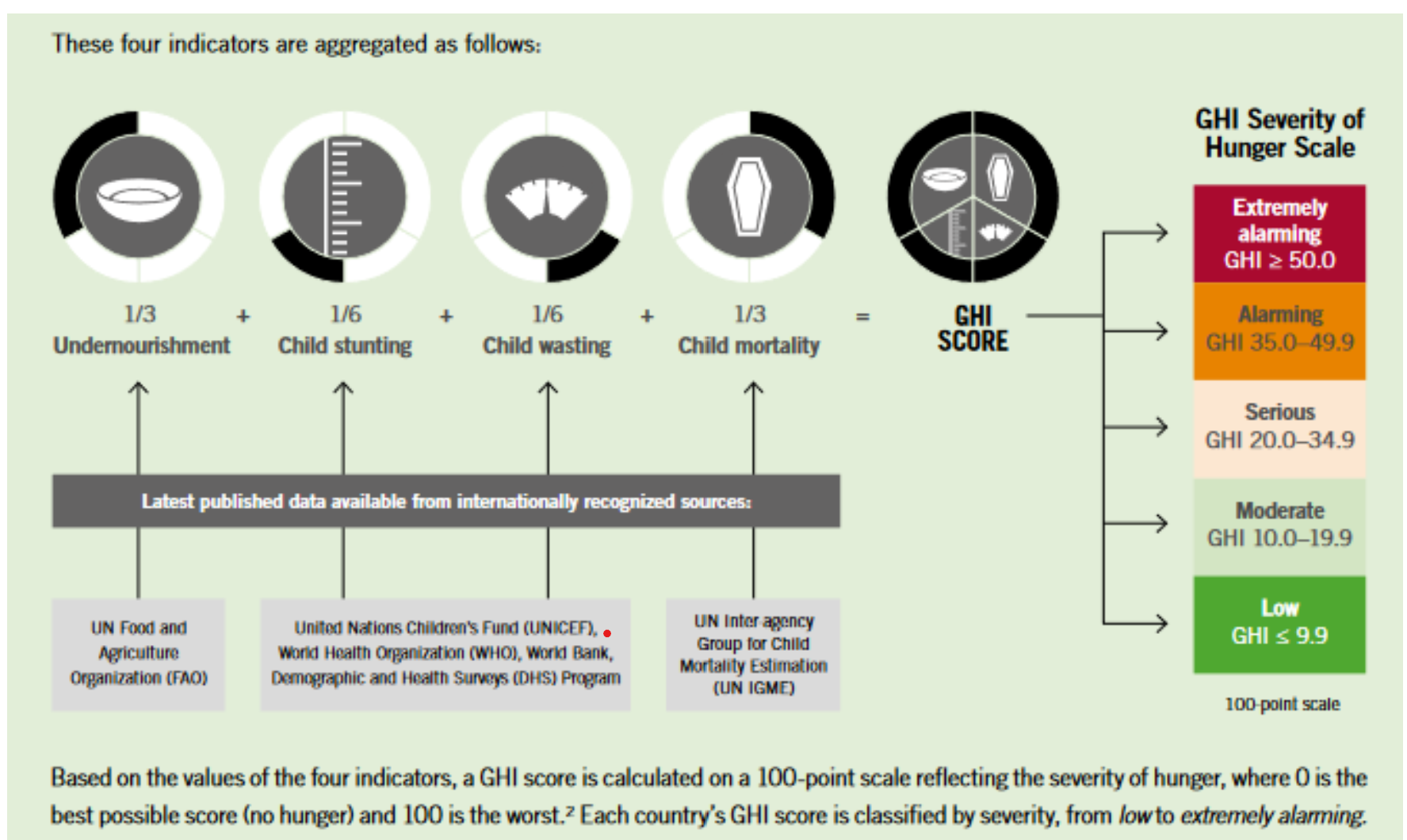

2. GHI is calculated based on a formula that combines four indicators that together capture the multidimensional nature of hunger:

- Undernourishment: the share of the population whose caloric intake is insufficient;

- Child stunting: the share of children under the age of five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition;

- Child wasting: the share of children under the age of five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition; and

- Child mortality: the share of children who die before their fifth birthday, reflecting in part the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments.

3. The 2024 GHI reflects that multiple factors are posing challenges in attaining Zero Hunger. The challenges include large-scale armed conflicts, climate change indicators that are worsening faster than expected, high food prices, market disruptions, economic downturns, and debt crises in many low- and middle-income countries.

4. The report highlights the link between Gender inequality, climate change, and hunger. Gender is intertwined with climate and food security challenges in ways that respective policies and interventions often ignore. Women and girls are typically hardest hit by food insecurity and malnutrition. They also suffer disproportionately from the effects of weather extremes and climate emergencies.

5. Six countries – Somalia, Yemen, Chad, Madagascar, Burundi, and South Sudan- have levels of hunger considered alarming. This is the result of widespread human misery, undernourishment, and malnutrition.

What is Hunger?

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines hunger as food deprivation, or undernourishment, as the habitual consumption of too few calories to provide the minimum dietary energy an individual requires to live a healthy and productive life, given that person’s sex, age, stature, and physical activity level.

6. India ranked 105th out of 125 countries in the Global Hunger Index 2024, with a score of 27.3, indicating a serious level of hunger. Child wasting is particularly high in India. Child undernutrition in India goes hand in hand with the poor nutritional status of mothers, suggesting an intergenerational pattern of undernutrition and underscoring the need for attention to maternal health nutrition and infant feeding.

7. India’s GHI score of 27.3 is a cause for concern, especially when compared to its South Asian neighbours like Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, which fall into the “moderate” category

8. The performance of India on various parameters of GHI:

- 13.7 per cent of India’s population suffers from undernourishment,

- 35.5 per cent of children under the age of five are stunted

- 18.7 per cent experience child wasting and

- 2.9 per cent of children do not reach their fifth birthday.

9. The policy recommendations made in the document include strengthening accountability to international law and the enforceability of the right to adequate food, promoting gender-transformative approaches to food systems and climate policies and programs, and making investments that integrate and promote gender, climate, and food justice.

National Family Health Survey

1. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) in India provides estimates of underweight, (low weight for age), stunting (low height for age), and wasting (low weight for height). These conditions affect preschool children (those less than 6 years of age) disproportionately and compromise a child’s physical and mental development while also increasing the vulnerability to infections.

2. According to the NFHS 5, the percentage of stunted, wasted, and underweight children is 36 per cent, 19 per cent and 32 per cent respectively.

(Thought Process: These data can be incorporated in your Mains Answer Writing to enrich your content.)

3. NFHS 5 highlighted that among mothers with a child between ages 6-23 months, 18 per cent reported that their child did not eat any food whatsoever — referred to as “zero-food” — in the 24 hours preceding the survey. The zero-food prevalence was 30 per cent for infants aged 6-11 months, remains worryingly high at 13 per cent among the 12-17 months old, and persists even among 18-23 months-old children at 8 per cent.

Hidden Hunger

In India, we suffer largely from “hidden hunger” which does not always manifest itself in an emaciated appearance. It is a hunger caused by the constant or recurrent lack of food of sufficient quality and quantity. It is the deprivation of vitamins and minerals, essential micronutrients that are necessary for proper growth, physical fitness, and mental development.

4. Going without food for an entire day at this critical period of a child’s development raises serious concerns related to severe food insecurity. According to the World Health Organisation, at six months of age, 33 per cent of the daily calorie intake is expected to come from food. This proportion increases to 61 per cent at 12 months of age. The recommended calorie percentages mentioned here are the minimum amount that should come from food.

5. India has a challenging task in attaining the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 of “zero hunger”. Mission Poshan 2.0, the overarching flagship programme dedicated to maternal and child nutrition, has evolved in the right direction by targeting SDG 2 “zero hunger” and focusing on food-based initiatives, including its flagship supplementary nutrition programme service as mandated by the 2013 National Food Security Act.