Rat-hole mining

- 13 Jan 2025

In News:

In Dima Hasao district of Assam, at least nine workers aged between 26 and 57 were trapped in a coal “rat-hole” mine after it was flooded with water. Three miners trapped in a flooded coal mine were confirmed dead, while six remained stuck. Later an Indian Navy team, including deep-sea divers, arrived at the site, where the water level inside the pit is 200 feet deep.

Key Takeaways:

- Rat-hole mining is a method of extracting coal from narrow, horizontal seams, prevalent in Meghalaya. The term “rat hole” refers to the narrow pits dug into the ground, typically just large enough for one person to descend and extract coal.

- Once the pits are dug, miners descend using ropes or bamboo ladders to reach the coal seams. The coal is then manually extracted using primitive tools such as pickaxes, shovels, and baskets.

- Types of Rat-hole mining:

- Side-cutting mining: In the side-cutting procedure, narrow tunnels are dug on the hill slopes and workers go inside until they find the coal seam. The coal seam in the hills of Meghalaya is very thin, less than 2 m in most cases.

- Box-cutting mining: In the other type of rat-hole mining, called box-cutting, a rectangular opening is made, varying from 10 to 100 sqm, and through that a vertical pit is dug, 100 to 400 feet deep. Once the coal seam is found, rat-hole-sized tunnels are dug horizontally through which workers can extract the coal.

- Concerns associated with Rat-hole mining: Rat-hole mining poses significant environmental and safety hazards. This method of mining has faced severe criticism due to its hazardous working conditions, and numerous accidents leading to injuries and fatalities.

- The mines are typically unregulated, lacking safety measures such as proper ventilation, structural support, or safety gear for the workers. Additionally, the mining process can cause land degradation, deforestation, and water pollution. Despite attempts by authorities to regulate or ban such practices, they often persist due to economic factors and the absence of viable alternative livelihoods for the local population.

- Notably, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) banned Rat-hole mining in 2014, and retained the ban in 2015, on grounds of it being unscientific and unsafe for workers. The order was in connection with Meghalaya, where this remained a prevalent procedure for coal mining. The state government then appealed the order in the Supreme Court.

Role of Rat-Hole Mining in Uttarkashi Tunnel Rescue

- The rat-hole mining practice, banned for being unsafe, helped in the rescue operation of 41 workers trapped in the collapsed Silkyara-Barkot tunnel in Uttarakhand in 2023.

- Rat-hole miners were called in after the auger machine that was drilling through the debris broke. Rescuers then tried cutting through the blade stuck inside the rescue pipes and removing it piece by piece. As large metal pieces hindered the machine drilling, the rescuers went ahead with rat-hole mining.

- It was a test of grit and perseverance – for men on both sides of the 57 metres of debris – as the rescue operation suffered one setback after another. In the end, it was miners who dug through the last 12 metres and reached the trapped men.

Selection Process for Chief Election Commissioner (CEC)

- 12 Jan 2025

In News:

The Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Term of Office) Act, 2023 represents a significant shift in the process of selecting the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) and other Election Commissioners (ECs) in India. Traditionally, the senior-most Election Commissioner automatically ascended to the position of CEC. However, the new law introduced in December 2023 widens the scope for selection, allowing for a more transparent process with an expanded pool of candidates.

Key Features of the Act:

- Election Commission Structure: The Election Commission of India is constituted by the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) and two other Election Commissioners (ECs). The President of India appoints these members, with the number of ECs fixed periodically.

- Appointment Process: The Act mandates that the CEC and ECs are appointed by the President based on recommendations from a Selection Committee. This committee comprises:

- The Prime Minister (Chairperson),

- The Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha (or leader of the largest opposition party),

- A Union Cabinet Minister appointed by the Prime Minister.

- Search Committee: A Search Committee, chaired by the Minister of Law and Justice, prepares a panel of five candidates. The Selection Committee may choose from this panel or opt for someone outside of it.

- Eligibility Criteria:

- Candidates must have integrity and experience in election management.

- They should be or have been Secretary-level officers or equivalent.

- Term and Reappointment:

- The term of CEC and ECs is six years or until they turn 65 years.

- They cannot be re-appointed after their term.

- Salary and Pension: The salary, allowances, and conditions of service of CEC and ECs are equivalent to those of a Cabinet Secretary.

- Removal Process:

- The CEC can be removed in the same manner as a Supreme Court Judge.

- ECs can be removed only on the recommendation of the CEC.

Departure from Tradition:

Traditionally, the next CEC was the senior-most Election Commissioner. However, the new law opens the process, allowing the Search Committee to consider candidates outside the current pool of Election Commissioners. This widens the net and may lead to a more transparent and inclusive selection.

Concerns and Criticisms: While the Act aims to improve the selection process, it has faced scrutiny and concerns, particularly about the independence of the Election Commission:

- Government Influence: The inclusion of the Leader of Opposition in the Selection Committee is a positive step, but critics argue that the final decision may still be influenced by the government. The government’s dominance in the Selection Committee could potentially affect the neutrality of the Commission.

- Exclusion of the Chief Justice of India (CJI): The Supreme Court's 2023 ruling had recommended including the CJI in the committee, but the new Act excludes the CJI. This has raised concerns about the balance of power and the credibility of the Election Commission.

- Risk of Partisanship: Former CEC O.P. Rawat expressed concerns that political changes might influence decisions, leading to a compromised credibility of the Election Commission.

Legal Challenges: Petitions challenging the exclusion of the CJI from the Selection Committee are currently pending before the Supreme Court, which is expected to address them in February 2025.

Historical Context and Legal Backdrop:

- Article 324 of the Indian Constitution provides for the appointment of CEC and ECs by the President, but this is subject to laws passed by Parliament.

- In 2023, the Supreme Court intervened in response to the growing concerns over the executive's unilateral control over these appointments. The Court's ruling in the Anoop Baranwal v. Union of India case led to the formation of a committee comprising the Prime Minister, Leader of Opposition, and CJI until Parliament could enact a law. This resulted in the Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners Act, 2023, which was aligned with the Court's directions.

Implications and Way Forward:

- Potential Government Influence: While the law aims to reduce executive control, the dominant role of the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition could still allow the government to influence appointments, especially in contentious times.

- Suggestions for Reform: The Law Commission had recommended a broader selection committee, including the CJI, to ensure a balanced and impartial selection process. The National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC) also suggested a committee comprising key political figures, including the Leader of Opposition in the Rajya Sabha and the Speaker of Lok Sabha.

- Integrity of the Election Commission: The credibility and impartiality of the Election Commission are vital for ensuring free and fair elections. It is crucial to ensure that the appointment process not only appears fair but is also free from political interference.

Conclusion:

The Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Term of Office) Act, 2023 introduces a reformed approach to the selection of the Election Commission members. While the law aims for greater transparency, it also raises concerns regarding government influence and independence. The Supreme Court’s review of the exclusion of the CJI from the Selection Committee will be pivotal in determining the future trajectory of the Election Commission’s appointment process. The evolving legal and institutional dynamics will play a significant role in shaping the electoral reforms in India.

Glass Ceiling Cracks: Women's Rising Role in the 2024 Lok Sabha Elections

- 28 Dec 2024

Introduction:

The 2024 Lok Sabha elections marked a significant step forward for women’s participation in Indian politics. With 800 women candidates contesting across 390 constituencies, this was the highest ever since the 1957 general elections. This surge in women candidates has been a positive reflection of the evolving role of women in India's democratic processes.

Increase in Women Candidates:

- A total of 800 women candidates participated in the 2024 elections, up from 726 in 2019.

- The number of constituencies with no female candidate dropped to a historic low of 152, from 171 in 2019.

- However, despite the rise in participation, only 74 women won, while 629 forfeited their deposits.

Regional Variations:

- The highest number of women candidates were from Maharashtra (111), followed by Uttar Pradesh (80) and Tamil Nadu (77).

- Some constituencies, like Baramati, Secunderabad, and Warangal, saw the highest participation of women, with eight candidates each.

Voter Turnout and Gender Dynamics:

- Women voters surpassed men in voter turnout for the second consecutive time, with 65.78% women casting their vote in 2024, compared to 65.55% of men.

- Assam’s Dhubri recorded the highest female voter turnout at 92.17%, reflecting increased female engagement in the electoral process.

Electoral Data and Gender Insights:

- In 2024, there were 47.63 crore female electors out of 97.97 crore total voters, making up 48.62% of the electorate, a slight increase from 2019.

- The number of female electors per 1,000 male voters reached 946, up from 926 in 2019, showing growing electoral inclusivity.

Challenges and Progress:

- Despite the gains in women’s representation, there remain several constituencies without any female candidates, notably in states like Uttar Pradesh (30 constituencies), Bihar (15), and Gujarat (14).

- Though women's participation has risen, the number of women who win remains disproportionately low, reflecting the challenges they face in a patriarchal political landscape.

Inclusion and Diversity:

- The 2024 elections also saw greater inclusivity, with a rise in third-gender electors, which increased by 23.5% to 48,272.

- Voter turnout among transgender voters nearly doubled, reaching 27.09% compared to 14.64% in 2019.

- Additionally, the number of persons with disabilities (PwD) electors increased to 90.28 lakh, showcasing broader electoral inclusivity.

Conclusion:

The 2024 Lok Sabha elections witnessed a remarkable increase in women’s participation, both as voters and candidates. While the journey toward full gender parity in politics continues, the trends from these elections indicate a growing shift toward more inclusive electoral processes. The data released by the Election Commission further underlines this progress, showing the increasing role of women in shaping India’s democratic future.

India-Sri Lanka Diplomatic Engagement

- 22 Dec 2024

In News:

The recent visit of Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) to India marked a significant moment in bilateral relations, as it was his first foreign trip since assuming office. The visit underscored key diplomatic exchanges and collaborations between the two countries, showcasing both areas of agreement and divergence.

Key Takeaways from AKD's Visit

Assurance on Anti-India Activities: One of the primary concerns for India was the use of Sri Lankan territory for activities detrimental to its security, particularly the presence of Chinese “research vessels” at Sri Lankan ports. President AKD assured Prime Minister Narendra Modi that Sri Lanka would not allow its territory to be used in ways that threaten India’s interests. This assurance is crucial, as it signals Sri Lanka's stance on maintaining regional stability, despite AKD’s perceived pro-China inclinations.

Tamil Minority Issue: Divergent Views: A notable divergence in their discussions was the issue of the Tamil minority in Sri Lanka. India has long advocated for the full implementation of the 13th Amendment to Sri Lanka’s Constitution, which would grant greater autonomy to the Tamil minority. However, AKD resisted this, reaffirming his opposition to the amendment’s full implementation. While India emphasized the importance of reconciliation and holding provincial elections, AKD focused on unity, sustainable development, and social protection, sidestepping any definitive commitments on the Tamil issue.

Sri Lanka's Assertive Diplomatic Posture: AKD’s strong parliamentary mandate has allowed him to adopt a more assertive diplomatic stance. This is evident not only in his handling of the Tamil issue but also in his approach to dealing with major powers like India and China. His administration appears to be prioritizing a more independent foreign policy, signaling a shift from previous administrations.

Bilateral Cooperation and Development Initiatives

The visit saw significant agreements on bilateral cooperation, particularly in development and connectivity. Both nations acknowledged the positive impact of India’s assistance in Sri Lanka’s socio-economic growth. Key projects discussed include:

- Indian Housing Project: Phases III and IV.

- Hybrid Renewable Energy Projects across three islands.

- High-Impact Community Development Projects.

- Digital collaborations, such as the implementation of Aadhaar and UPI systems in Sri Lanka.

Additionally, discussions focused on enhancing energy cooperation, including the supply of LNG, development of offshore wind power in the Palk Strait, and the high-capacity power grid interconnection. The resumption of passenger ferry services between key Indian and Sri Lankan ports was also a priority.

Defence and Security Cooperation

The two leaders agreed to explore a Defence Cooperation Framework and intensify collaboration on maritime surveillance, cyber security, and counter-terrorism. This aligns with India’s strategic interests in the region, as it seeks to ensure stability in the Indian Ocean and strengthen its defense ties with Sri Lanka.

Strategic Continuity Amid Leadership Change

Despite a change in leadership, the core strategic interests between India and Sri Lanka remain aligned. India views Sri Lanka’s stability as crucial to regional security, and both countries are focused on a mutually beneficial partnership. AKD’s emphasis on economic recovery and tackling corruption within Sri Lanka, as seen in his actions against political figures like Speaker Asoka Ranwala, further signals his determination to build a strong foundation for his government’s future.

Conclusion

President AKD’s visit highlighted the evolving dynamics of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy, marked by a more confident and independent approach in engaging with India. While challenges remain, especially regarding the Tamil issue, both countries have reaffirmed their commitment to deepening bilateral ties, with a focus on development, connectivity, and strategic cooperation.

MeitY relaxes AI compute procurement norms for Start-ups

- 09 Oct 2024

Overview

The Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY) has relaxed certain provisions related to the procurement of computing capacity for artificial intelligence (AI) solutions. This decision is part of the Rs 10,370 crore IndiaAI Mission, aimed at enhancing the country’s AI capabilities.

Key Relaxations

Annual Turnover Requirements

- Primary Bidders: Turnover requirement reduced from ?100 crore to ?50 crore.

- Non-Primary Consortium Members: Requirement halved from ?50 crore to ?25 crore.

Computing Capacity Adjustments

- The performance threshold for successful bidders has been revised:

- FP16 Performance: Reduced from 300 TFLOPS to 150 TFLOPS.

- AI Compute Memory: Reduced from 40 GB to 24 GB.

Importance of the Changes

These adjustments respond to concerns raised by smaller companies about exclusionary requirements that favored larger firms. The aim is to create an inclusive environment that allows start-ups to participate in the AI landscape.

AI Mission Goals

- Establish a computing capacity of over 10,000 GPUs.

- Develop foundational models with capacities exceeding 100 billion parameters.

- Focus on priority sectors such as healthcare, agriculture, and governance.

New Technical Criteria

- Companies must demonstrate experience in offering AI services over the past three financial years.

- Minimum billing of ?10 lakh required for eligibility.

Local Sourcing Requirements

- Components for cloud services must be procured from Class I or Class II local suppliers as per the ‘Make in India’ initiative:

- Class I Supplier: Domestic value addition of at least 50%.

- Class II Supplier: Local content between 20-50%.

Data Sovereignty and Service Delivery

- All AI services must be delivered from data centres located in India.

- Data uploaded to cloud platforms must remain within India's sovereign territory.

Implementation Strategy

- The Rs 10,370 crore plan will be implemented through a public-private partnership model.

- 50% viability gap funding has been allocated for computing infrastructure development.

Conclusion

The relaxations in AI compute procurement norms aim to support the growth of start-ups in India, fostering an environment conducive to innovation in artificial intelligence. With these changes, smaller companies are better positioned to contribute to the country's ambitious AI goals.

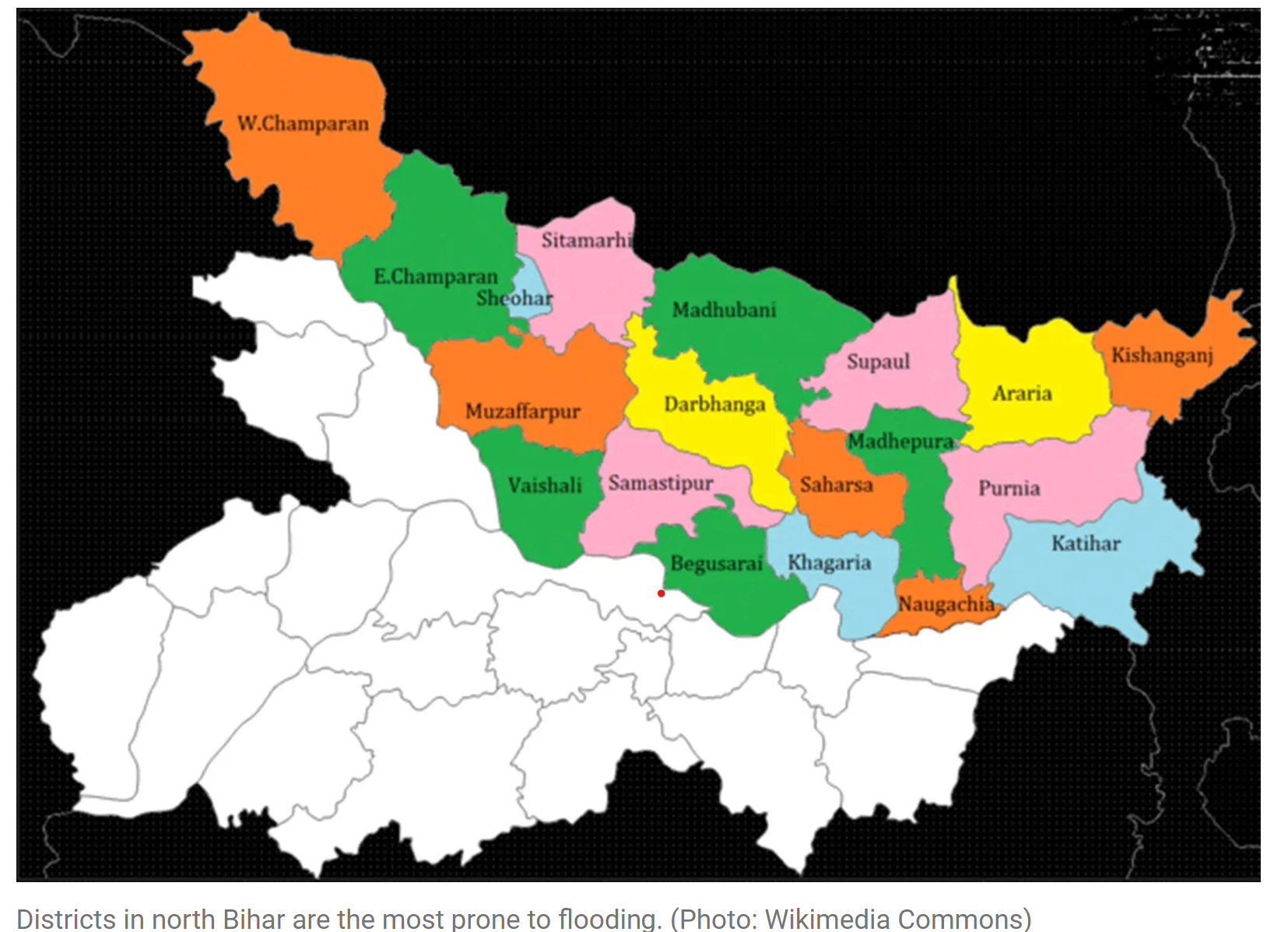

Bihar Under Water: An Analysis of Recurring Floods

- 04 Oct 2024

Overview

Bihar is one of India's most flood-prone states, with 11.84 lakh people affected by annual flooding. The state grapples with the devastation of homes, crops, and livestock, prompting a cycle of recovery only to face similar disasters each year.

Geographical Vulnerabilities

Flood-Prone Conditions

- Demographics: 76% of North Bihar’s population lives under the threat of floods.

- River Systems: The state is crisscrossed by multiple snow-fed and rain-fed rivers, contributing to various flood types:

- Flash Floods: Rapid onset due to rainfall in Nepal (lead time: 8 hours).

- River Floods: Slower onset with a lead time of 24 hours, lasting over a week.

- Drainage Congestion: Extended flooding throughout the monsoon season (lead time: over 24 hours).

- Permanent Waterlogging: Caused by various factors including sedimentation and encroachments.

Factors Contributing to Flooding

- Himalayan Rivers: Rivers like Kosi, Gandak, and Bagmati carry significant sediment, leading to overflow during heavy rains.

- Waterlogging Causes: Silted rivers, encroachment of drainage channels, and local topographical features called Chaurs contribute to permanent waterlogging.

Historical Management Efforts

Embankments and Their Impact

- Kosi River: Known as the "sorrow of Bihar," embankments built in the 1950s to control the Kosi’s flow have led to unintended consequences.

- Sediment Accumulation: Narrowing of the river’s course has caused sediment to build up, increasing the riverbed height and flood risks.

- Current Crisis: Recent flooding was exacerbated by the release of 6.6 lakh cusec of water from the Birpur barrage in Nepal, leading to multiple embankment breaches.

Economic and Social Effects

Impact on Livelihoods

- While annual flooding may not always lead to significant loss of life, the economic repercussions are severe:

- Damage to crops and infrastructure.

- Loss of livestock and economic migration outside the state.

- Government Spending: Approximately Rs 1,000 crore is allocated annually for flood management and relief efforts.

Proposed Solutions

Structural vs. Non-Structural Approaches

- Dam Construction: Proposals for new barrages on the Kosi and other rivers have been discussed, but require cooperation from Nepal.

- Need for Comprehensive Strategies: Experts suggest a dual approach:

- Structural Solutions: Dams and embankments.

- Non-Structural Solutions: Policy development, risk mitigation, and improved community awareness.

Emphasis on Risk Reduction

- The Flood Atlas of Bihar advocates for minimizing flood risk rather than relying solely on structural measures.

- Focus on enhancing early warning systems and community preparedness is crucial for effective flood management.

Conclusion

Bihar’s unique geographical and socio-economic landscape necessitates a multifaceted approach to flood management. While structural solutions like dams are important, the state must also invest in non-structural measures that promote resilience and reduce vulnerability among its population.

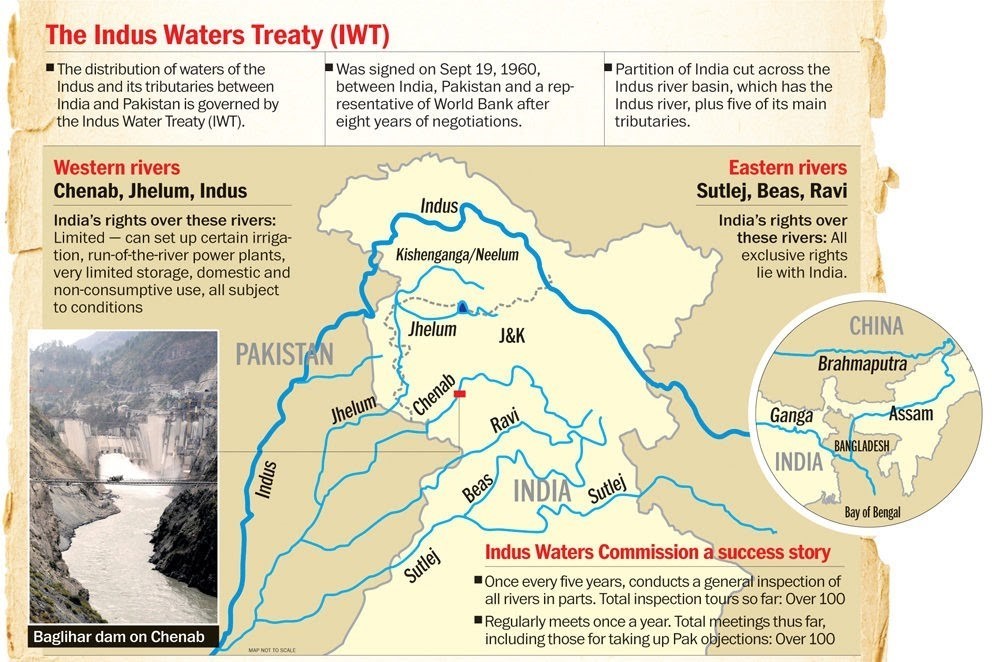

INDUS WATERS: INDIA FREEZES TALKS WITH PAKISTAN

- 20 Sep 2024

In News:

India has decided to halt all meetings of the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) until both governments engage in discussions to renegotiate the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), a decision communicated by a senior official. The last PIC meeting occurred in May 2022, and since January 2023, India has made four attempts to initiate talks with Pakistan, but these efforts have not received satisfactory responses.

The IWT, established in 1960 with the mediation of the World Bank, governs the sharing of six rivers between India and Pakistan. Under this treaty, India controls the waters of the Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas rivers, while Pakistan has rights to the Sindh, Jhelum, and Chenab rivers. The treaty mandates annual meetings of the PIC, which have continued despite ongoing conflicts between the two nations. However, India’s recent push for renegotiation threatens the stability of this long-standing arrangement.

India's Notice for Review of the Indus Waters Treaty

India formally issued a notice to Pakistan on August 30, 2023, seeking modifications to the IWT, citing "fundamental and unforeseen changes" that necessitate a reassessment of the agreement. This is not an isolated instance; India had previously requested a review in January 2023, attributing the need for change to Pakistan’s persistent intransigence regarding its obligations under the treaty.

Key reasons for India’s demand include:

- Changes in population demographics and environmental challenges.

- The necessity for clean energy development to meet emissions targets.

- The impact of ongoing cross-border terrorism, which India argues affects water management and security.

The notification highlights issues related to two contentious hydroelectric projects in Jammu & Kashmir—the Kishanganga and Ratle projects—over which Pakistan has raised objections, claiming they violate the IWT. India asserts that these projects are "run-of-the-river" schemes that do not significantly impede river flow.

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms Under the Treaty

The IWT outlines a structured dispute resolution mechanism, as detailed in Article IX. This mechanism involves three levels:

- First Level: Initial discussions occur at the PIC, where either party must inform the other of planned projects.

- Second Level: If differences remain unresolved, a Neutral Expert, appointed by the World Bank, is engaged to mediate.

- Third Level: Should the Neutral Expert fail to resolve the issue, the dispute escalates to the Court of Arbitration.

Historically, both countries have used these mechanisms, although recent years have seen significant contention. After a Pakistan-backed terror attack in Uri in 2016, India’s Prime Minister expressed the sentiment that “blood and water cannot flow together,” leading to the suspension of routine talks.

The World Bank has navigated a complex situation, receiving requests from both nations for adjudication on overlapping disputes. In December 2016, it paused these processes to encourage direct negotiations. Despite attempts to resume dialogue between 2017 and 2022, Pakistan’s reluctance to engage has further complicated matters.

Current Status and Future Implications

India’s formal notification and its call for renegotiation may set a precedent that challenges the existing framework of the IWT. The continuation of the PIC's activities hinges on a willingness from both governments to address these evolving concerns collaboratively. As tensions persist and environmental needs grow, the future of water-sharing arrangements in the region remains uncertain. The overarching goal for both nations will be to find a sustainable resolution that addresses emerging challenges while honoring the historical framework established by the IWT.

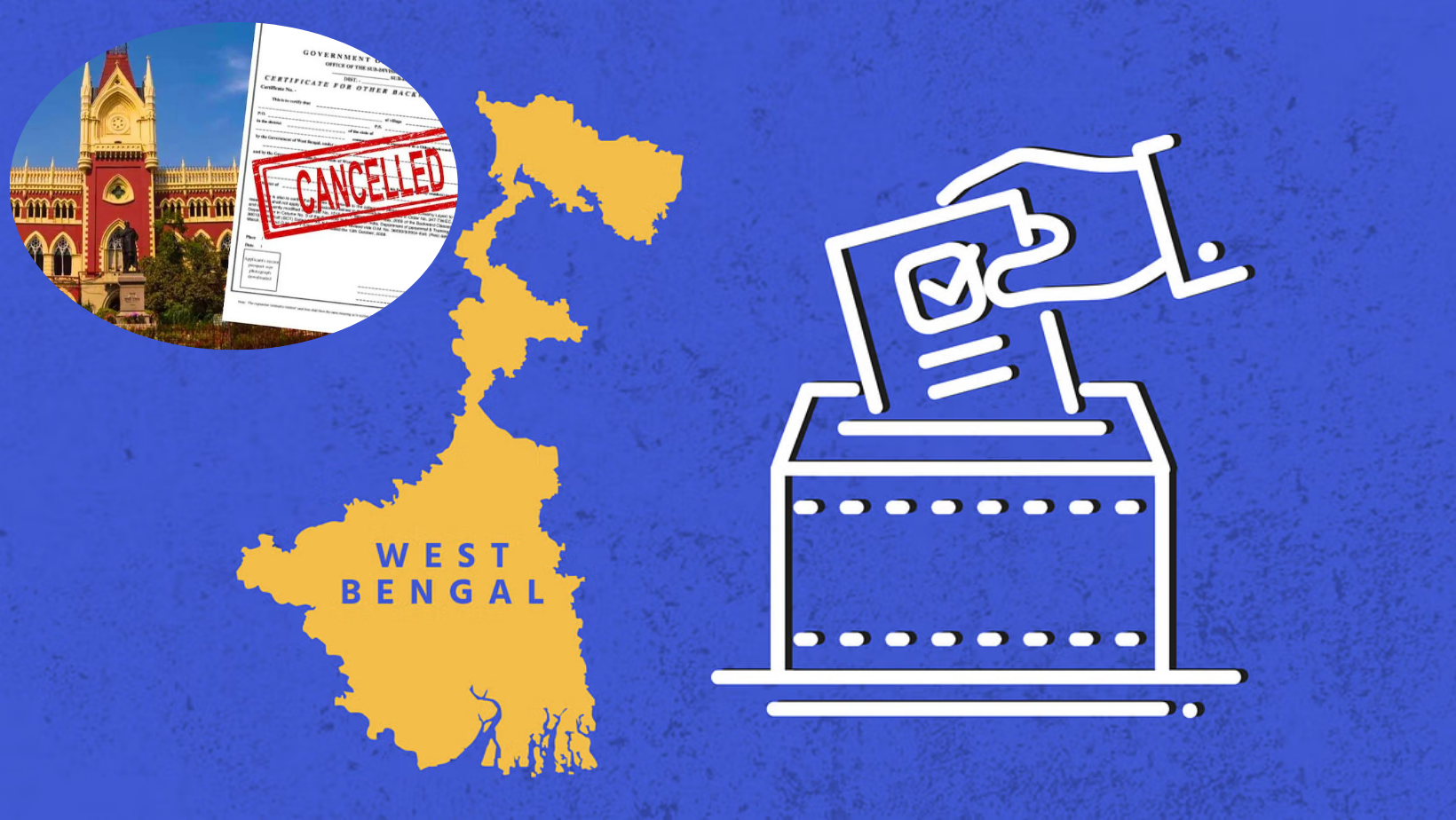

Religion Should Not be the Sole Reason for Granting Reservation

- 25 May 2024

Why is it in the News?

The Calcutta High Court has struck down a series of orders passed by the West Bengal government between March 2010 and May 2012 by which 77 communities (classes), 75 of which were Muslim, were given reservation under the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category.

Context:

- In a significant ruling on Wednesday, the Calcutta High Court dismissed all Other Backward Classes (OBC) certificates issued in West Bengal since 2010.

- A division bench of Justice Tapabrata Chakraborty and Justice Rajasekhar Mantha made this decision while addressing a public interest litigation (PIL) that challenged the process of granting OBC certificates.

- The court directed that a new list of OBCs should be created based on the West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes Act of 1993.

What is the Issue With OBC Certificates?

- In 2010, the West Bengal (WB) government issued notifications, on the recommendations of the West Bengal Backward Classes Commission, including 42 classes (41 from the Muslim community) as Other Backward Classes (OBCs), entitling them to reservation and representation in government employment under Article 16(4) of the Constitution.

- Also in 2010, an order was issued sub-categorizing the 108 identified OBCs in the state (66 pre-existing and 42 newly identified) into 56 OBC-A (more Backward) and 52 OBC-B (Backward) categories.

- In 2012, the West Bengal government included 35 classes (34 from the Muslim community) as OBCs.

- In 2013, the West Bengal Backward Classes (Other than Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) (Reservation of vacancies and posts) Act 2012 gave recognition to all 77 new OBCs.

- These orders and legislation were challenged in the Calcutta High Court on the grounds that the declaration of classes as OBCs was based purely on religion, the categorization was not based on any acceptable data, and the survey conducted by the Commission was unscientific.

The Calcutta High Court's Ruling on West Bengal's Reservation Policies:

- The court found that religion had been the sole basis for the state government to provide reservation, which is prohibited by the Constitution and court orders.

- The High Court heavily relied on the Supreme Court's judgment in Indra Sawhney v Union of India (Mandal judgment).

- In 1992, a nine-judge Bench held that OBCs cannot be identified and given reservation solely based on religion.

- The Supreme Court also held that all states must establish a Backward Classes Commission to identify and recommend classes of citizens for inclusion and exclusion in the state OBC list.

- The High Court noted that the Commission's recommendation had been made with "lightning speed" and without using any objective criteria to determine the backwardness of these classes.

- The court stated that there is no question that the said communities have been used as a political prop for vote bank politics.

- The court struck down some provisions of West Bengal's 2012 Act, including:

- The provision allowed the state government to sub-classify OBC reservations into OBC-A and OBC-B categories.

- The provision allows the state to amend the Schedule of the 2012 Act to add to the list of OBCs.

- The court held that sub-classification is meant to address different levels of deprivation faced by different communities and could only be done based on scientific data.

- Since the Commission acknowledged that the government did not consult it prior to sub-classification within OBC, the court ruled that the state government must consult the Commission to create a fair and unbiased classification.

The Position on Religiously-Based Reservations in the Constitution and Court Orders:

The Constitution of India:

- Article 15(1) specifically prohibits the state from discriminating against citizens on grounds only of religion and caste (along with sex, race, and place of birth).

- Article 16(2) specifically prohibits the state from discriminating against citizens on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them, in respect of any employment or office under the State.

The Observations of the Supreme Court:

- In M R Balaji (1962), the SC held that while castes among Hindus may be an important factor to take into account when assessing the social backwardness of certain groups or classes of citizens, it cannot be the only test in this regard.

- In E P Royappa vs State Of Tamil Nadu (1973), the SC held that equality is a dynamic concept and cannot be confined within traditional limits.

- In State of Kerala vs N M Thomas (1975), the SC held that the crucial word 'only' in Articles 15 and Article 16 implies that if a religious, racial, or caste group constitutes a weaker section (under Article 46) or constitutes a backward class, it would be entitled to special provisions for its advancement.

- The SC in Indra Sawhney (1992) laid down that any social group if found to be backward under the same criteria as others, will be entitled to be treated as a backward class.

What are the Current Provisions of Reservation?

- The current provisions of reservation in India stem from the Constituent Assembly's decision to provide employment reservations for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes under Article 16(4A) of the Constitution.

- Initially approved for a period of 10 years, these reservations have been renewed annually ever since.

- Notably, Christian and Muslim communities within the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes do not receive reservation benefits.

- The decision not to extend reservation to religious minorities was influenced by the partition, as reflected in Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel's presentation of a special sub-committee report in 1949, addressing the issues faced by minority populations in East Punjab and West Bengal.

- The committee, which included Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, KM Munshi, and Ambedkar, concluded that the country's conditions had changed to such an extent that "in the context of independent India and the present circumstances, it is no longer appropriate to reserve seats for Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, or any other religious minority."

- They believed that reservations for religious communities "may lead to some degree of separatism and, to an extent, contradict the concept of a secular democratic state."

- They argued that the fundamental rights of freedom of religion and the right of minorities to maintain their own educational institutions were sufficient safeguards for protecting minorities.

- However, the Advisory Committee agreed that "the specific situation of the Scheduled Castes would make it necessary to grant them reservation for the originally decided ten-year period."

- Ambedkar attempted to resolve several positions on the caste question by introducing the concept of backwardness and reservation as methods of creating a society beyond caste.

Arguments Related to Religion-based Reservation in India:

Arguments in Favour of Religion-Based Reservations in India:

- Socio-Economic Backwardness: According to the Sachar Committee Report, Muslims in India lag behind other communities in terms of socio-economic indicators such as education, employment, and income.

- Reservations can help in bridging this gap.

- Constitutional Mandate: The Indian Constitution provides for affirmative action for socially and educationally backward classes irrespective of religious and cultural denomination.

- Ensuring Adequate Representation: Reservations can ensure adequate representation of underrepresented religious groups in employment, education, and other fields.

Arguments Against Religion-Based Reservations in India:

- Secularism: Critics argue that providing reservations based on religion goes against the principle of secularism enshrined in the Indian Constitution, which advocates equal treatment of all religions by the state.

- Undermining National Unity: Religion-based reservations could undermine national unity as it could lead to resentment and division among different communities.

- Economic Criteria: Reservations should be based solely on economic criteria rather than religion, to ensure that benefits reach those who are truly economically disadvantaged, irrespective of their religion.

- Administrative Challenges: Implementing reservations based on religion could pose administrative challenges, such as determining the criteria for identifying beneficiaries and preventing misuse of the system.

Way Forward:

- Socio-Economic Criteria: Instead of religion, reservations could be based on socio-economic criteria, ensuring that benefits reach the most disadvantaged individuals regardless of their religion.

- Empowerment Through Education: Focus on improving educational infrastructure and providing skill development programs to empower the backward communities and enhance their socio-economic status.

- Inclusive Policies: Implement inclusive policies that address the specific needs of the backward religious communities in areas such as education, employment, and healthcare, without resorting to religious-based reservations.

- Dialogue and Consensus: Engage in a dialogue involving all stakeholders to arrive at a consensus to address the socio-economic challenges faced by the various communities, ensuring that any measures taken are in line with constitutional values and principles.

Conclusion

While recognizing the socio-economic disparities faced by various religious communities in India, the emphasis on inclusive policies based on socio-economic criteria emerges as pivotal. By prioritizing education empowerment, promoting dialogue, and fostering consensus, India can navigate towards a more equitable and inclusive society. By steering away from religion-based reservations and focusing on holistic development, India can uphold its constitutional values while addressing the diverse needs of its population.

A Message on the Model Code of Conduct for Leaders – From Mahabharata and Beyond

- 24 May 2024

Why is it in the News?

In a democracy, while elections are imperative, it's equally crucial for both the populace and our leaders to retain their moral integrity, as a loss of ethical grounding could result in repercussions that extend far beyond the periodic act of political selection.

Context:

- Satyameva Jayate ("Truth alone triumphs") from the Mundaka Upanishad was adopted as the national motto on January 26, 1950, the day India became a Republic.

- A day earlier, the country's Election Commission was formed with the primary responsibility of enabling citizens to exercise their democratic right to choose a government.

- The Election Commission is expected to provide a level playing field so that candidates, political parties, and their campaigners do not unduly influence voters through excessive use of money, force, or dishonesty.

About The Model Code of Conduct (MCC):

- The Election Commission of India introduced the Model Code of Conduct with the hope that it would encourage self-control among political stakeholders.

- The 2019 Manual emphasized that those seeking public office should behave in a way worthy of being emulated by others.

- The Commission considers the Code an important contribution by political parties to democracy.

- It expects parties to exhibit model behaviour in their actions and rhetoric.

- However, reality often deviates from this expectation. Political discourse sometimes degrades into coarse and ignoble exchanges.

- This has led to debates on whether it should be called a moral code rather than just a model code.

The Complexity of Truth from a Philosophical Perspective:

- Francis Bacon's Essay of Truth commences with Pilate's profound questioning, "What is truth?" - a query that resonates through the ages, its answer shrouded in layers of complexity.

- This intricate nature finds symbolic representation in the Ashokan pillar's trio of visible lions, embodying the three dimensions of truth: my viewpoint, your perspective, and an objective third-person narrative.

- Yet, there exists a fourth, unseen dimension - that of absolute truth, often perceived as knowable only to a higher power.

- Amidst this philosophical labyrinth, the Election Commission of India (ECI) navigates the realm of human imperfection, striving to enforce the Model Code of Conduct (MCC) – a framework designed to curb dishonest practices during the electoral process.

- However, expecting individuals to adhere to this model solely for the duration of elections, if they have not upheld such principles in their daily lives, could be considered a naive endeavor.

The Intersection of Morality and Law in the Electoral Process:

- Foundations of the Model Code of Conduct (MCC):

- At the core of the Model Code of Conduct lies a fundamental interplay between legal requirements and moral expectations.

- Morality governs individual behaviour based on notions of right and wrong, often rooted in cultural, religious, or personal beliefs.

- Law, conversely, comprises rules established by a governing authority to regulate conduct and ensure order and justice within society.

- Philosophical perspectives offer valuable insights into this dynamic. Immanuel Kant's philosophy distinguishes between morality and law, viewing moral actions as those driven by a sense of duty, while societal rules govern legal actions.

- Utilitarianism, advocated by thinkers like Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, evaluates actions based on their consequences and their contribution to the overall well-being of society.

- In the context of the Model Code of Conduct, this perspective suggests that political behaviour should be assessed not only against legal standards but also by its broader impact on societal harmony and democratic health.

- Legal Framework and Enforcement:

- The legal framework encompassing the Model Code of Conduct includes specific provisions in the Indian Penal Code and the Representation of the People Act, 1951.

- These laws define actions that constitute corrupt practices and electoral offences, providing a legal basis for enforcing the Code.

- However, the intersection of morality and law within this framework presents unique challenges.

- In legal terms, "mens rea" refers to the intention or knowledge of wrongdoing, and establishing mens rea is crucial for proving guilt in many cases.

- The Model Code of Conduct implicitly addresses mens rea by prohibiting actions intended to manipulate or deceive voters, such as false promises or appeals to communal sentiments.

- Sections 123(3) and 123(3A) of the Representation of the People Act classify appeals to caste or communal feelings as corrupt practices, punishable under the law.

- Similarly, Section 125 prohibits promoting enmity between different groups in connection with elections.

- These legal provisions aim to curb divisive tactics and uphold the ethical conduct envisioned by the Model Code of Conduct.

- However, enforcement requires clear evidence linking the actions to the intent of influencing electoral outcomes.

Ethical Reflection in the Electoral Process & Lesson from Mahabharata:

- Upholding Integrity: The imperative for ethical reflection in the electoral process stems from the need to uphold the integrity of democracy itself.

- The conduct of elections must align with the core values of truth and fairness that underpin the democratic ethos.

- Ethical Lesson from Mahabharata: The story of Yudhishthira in the Mahabharata, who lost his moral high ground despite technically telling the truth, underscores the importance of ethics over mere adherence to rules.

- Ethics in elections transcends simply following the law; it involves adhering to higher standards of honesty, integrity, and fairness.

- Moral Soundness over Legal Compliance: Ethical reflection ensures that political actions and decisions are not just legally compliant but also morally sound.

- This is particularly crucial in a democracy, where the legitimacy of the government is derived from the consent of the governed, and this consent must be obtained through fair means.

- Safeguarding Democratic Norms: When ethical standards are compromised, democratic norms such as transparency, accountability, and fairness are weakened.

- This erosion can lead to a governance crisis where the authority of elected officials is questioned, undermining the very foundation upon which democracy rests.

Conclusion

“Satyameva Jayate” is not just India’s motto however it encapsulates a guiding principle that should permeate the conduct of individuals and institutions alike. The Election Commission of India's efforts to enforce the Model Code of Conduct reflect an ongoing struggle to strike a delicate balance between legal enforcement and moral persuasion. For a truly democratic society to thrive, this equilibrium must be continually sought and maintained. The pursuit of political power must never be allowed to erode the foundational value of truth upon which the democratic edifice rests. By upholding the principle of Satyameva Jayate, not just in rhetoric but in action, the integrity of the electoral process and the sanctity of democratic norms can be safeguarded, ensuring that the will of the people remains the cornerstone of governance.