Digital Governance in India

- 16 Jan 2025

In News:

India is making significant strides toward digital governance, an initiative aimed at enhancing both citizen services and the capabilities of government employees. This transition to a digitally-driven framework is designed to improve the efficiency, transparency, and accountability of government operations, positioning India as a global leader in modern governance practices.

What is Digital Governance?

Digital governance refers to the application of technology to enhance the functioning of government processes. By integrating digital tools and platforms, it aims to streamline administrative operations, reduce inefficiencies, and improve public service delivery. This approach also extends to ensuring greater transparency and accountability in government dealings.

Key Initiatives in Digital Governance

India has launched several critical initiatives to modernize governance through digital means. Some of the key programs include:

- iGOT Karmayogi Platform: The iGOT Karmayogi platform is a government initiative to provide online training to public employees. It aims to enhance public administration skills, foster expertise in data analytics, and equip employees with the necessary tools in digital technologies. This initiative aims to prepare government personnel to handle the challenges of a digitally evolving governance landscape.

- e-Office Initiative: The e-Office program is designed to reduce paper-based work by digitizing workflows within government departments. This initiative facilitates real-time communication among offices and ensures more efficient and transparent management of tasks. It also helps streamline decision-making processes and improves the speed of governance operations.

- Government e-Marketplace (GeM): The Government e-Marketplace (GeM) is an online platform developed to optimize procurement processes. It allows government agencies to procure goods and services efficiently, transparently, and with accountability. This platform has contributed to reducing corruption and ensuring that government purchases represent the best value for public money.

- Cybersecurity Training for Employees: As digital operations increase, ensuring the safety of sensitive data is paramount. The cybersecurity training program for government employees is designed to enhance their ability to recognize and respond to potential cyber threats. This initiative ensures data protection, safe online practices, and cyber resilience across digital governance platforms.

Challenges in Implementing Digital Governance

Despite its benefits, India faces several challenges in the successful implementation of digital governance. These obstacles must be addressed to unlock the full potential of technology-driven governance.

- Resistance to Technological Change: One of the key barriers to digital transformation in government is the resistance among employees to adopt new technologies. Many government officials remain accustomed to traditional, paper-based processes and are reluctant to transition to digital systems due to concerns about complexity and job security.

- Digital Divide in Rural Areas: While urban regions in India have better access to high-speed internet and digital infrastructure, many rural areas face significant digital divide challenges. Limited access to technology hampers the successful implementation of digital governance in these regions, restricting equitable service delivery across the country.

- Cybersecurity Risks: The rise of digital operations in governance increases the risk of cyberattacks and data breaches. With government data being digitized, the threat of cybercrimes becomes more pronounced, making it critical to implement robust cybersecurity measures and data protection strategies to safeguard sensitive information.

- Lack of Incentives for Training Outcomes: Although government employees are encouraged to take part in training programs such as iGOT Karmayogi, the absence of clear incentives to complete these programs can undermine their effectiveness. Establishing tangible rewards or career progression linked to the successful completion of training would encourage employees to fully engage in capacity-building initiatives.

Solutions to Overcome Challenges

To ensure the success of digital governance, several strategies must be put in place to address the challenges identified.

- Foster Innovation-Friendly Environments: Promoting an innovation-friendly culture within government offices can help reduce resistance to new technologies. Encouraging employees to engage with digital tools, offering regular training, and providing ongoing support will facilitate a smoother transition to a technology-driven governance system.

- Invest in Digital Infrastructure for Rural Areas: Addressing the digital divide requires significant investment in digital infrastructure in rural and remote areas. Ensuring that these regions have reliable internet access and the necessary technological resources will empower citizens across India to benefit from digital governance.

- Continuous Capacity-Building Programs: Establishing continuous training programs for government employees will ensure that they remain up-to-date with the latest technological trends. Regular updates to training content will help employees stay prepared to handle emerging challenges in digital governance.

- Strengthen Cybersecurity Protocols: To mitigate cybersecurity risks, it is essential to implement stringent cybersecurity measures across all levels of government operations. This includes regular cybersecurity awareness programs, proactive threat management systems, and rigorous data protection protocols to safeguard both government data and citizens’ personal information.

Conclusion

India’s shift towards digital governance represents a significant step toward modernizing administrative systems, enhancing transparency, and improving service delivery to citizens. However, challenges such as resistance to change, the digital divide, cybersecurity risks, and the lack of clear incentives for training must be addressed. By investing in digital infrastructure, offering continuous training programs, and reinforcing cybersecurity measures, India can create an effective and secure framework for digital governance that benefits both its citizens and the government workforce.

Selection Process for Chief Election Commissioner (CEC)

- 12 Jan 2025

In News:

The Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Term of Office) Act, 2023 represents a significant shift in the process of selecting the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) and other Election Commissioners (ECs) in India. Traditionally, the senior-most Election Commissioner automatically ascended to the position of CEC. However, the new law introduced in December 2023 widens the scope for selection, allowing for a more transparent process with an expanded pool of candidates.

Key Features of the Act:

- Election Commission Structure: The Election Commission of India is constituted by the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) and two other Election Commissioners (ECs). The President of India appoints these members, with the number of ECs fixed periodically.

- Appointment Process: The Act mandates that the CEC and ECs are appointed by the President based on recommendations from a Selection Committee. This committee comprises:

- The Prime Minister (Chairperson),

- The Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha (or leader of the largest opposition party),

- A Union Cabinet Minister appointed by the Prime Minister.

- Search Committee: A Search Committee, chaired by the Minister of Law and Justice, prepares a panel of five candidates. The Selection Committee may choose from this panel or opt for someone outside of it.

- Eligibility Criteria:

- Candidates must have integrity and experience in election management.

- They should be or have been Secretary-level officers or equivalent.

- Term and Reappointment:

- The term of CEC and ECs is six years or until they turn 65 years.

- They cannot be re-appointed after their term.

- Salary and Pension: The salary, allowances, and conditions of service of CEC and ECs are equivalent to those of a Cabinet Secretary.

- Removal Process:

- The CEC can be removed in the same manner as a Supreme Court Judge.

- ECs can be removed only on the recommendation of the CEC.

Departure from Tradition:

Traditionally, the next CEC was the senior-most Election Commissioner. However, the new law opens the process, allowing the Search Committee to consider candidates outside the current pool of Election Commissioners. This widens the net and may lead to a more transparent and inclusive selection.

Concerns and Criticisms: While the Act aims to improve the selection process, it has faced scrutiny and concerns, particularly about the independence of the Election Commission:

- Government Influence: The inclusion of the Leader of Opposition in the Selection Committee is a positive step, but critics argue that the final decision may still be influenced by the government. The government’s dominance in the Selection Committee could potentially affect the neutrality of the Commission.

- Exclusion of the Chief Justice of India (CJI): The Supreme Court's 2023 ruling had recommended including the CJI in the committee, but the new Act excludes the CJI. This has raised concerns about the balance of power and the credibility of the Election Commission.

- Risk of Partisanship: Former CEC O.P. Rawat expressed concerns that political changes might influence decisions, leading to a compromised credibility of the Election Commission.

Legal Challenges: Petitions challenging the exclusion of the CJI from the Selection Committee are currently pending before the Supreme Court, which is expected to address them in February 2025.

Historical Context and Legal Backdrop:

- Article 324 of the Indian Constitution provides for the appointment of CEC and ECs by the President, but this is subject to laws passed by Parliament.

- In 2023, the Supreme Court intervened in response to the growing concerns over the executive's unilateral control over these appointments. The Court's ruling in the Anoop Baranwal v. Union of India case led to the formation of a committee comprising the Prime Minister, Leader of Opposition, and CJI until Parliament could enact a law. This resulted in the Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners Act, 2023, which was aligned with the Court's directions.

Implications and Way Forward:

- Potential Government Influence: While the law aims to reduce executive control, the dominant role of the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition could still allow the government to influence appointments, especially in contentious times.

- Suggestions for Reform: The Law Commission had recommended a broader selection committee, including the CJI, to ensure a balanced and impartial selection process. The National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC) also suggested a committee comprising key political figures, including the Leader of Opposition in the Rajya Sabha and the Speaker of Lok Sabha.

- Integrity of the Election Commission: The credibility and impartiality of the Election Commission are vital for ensuring free and fair elections. It is crucial to ensure that the appointment process not only appears fair but is also free from political interference.

Conclusion:

The Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Term of Office) Act, 2023 introduces a reformed approach to the selection of the Election Commission members. While the law aims for greater transparency, it also raises concerns regarding government influence and independence. The Supreme Court’s review of the exclusion of the CJI from the Selection Committee will be pivotal in determining the future trajectory of the Election Commission’s appointment process. The evolving legal and institutional dynamics will play a significant role in shaping the electoral reforms in India.

NITI Aayog Celebrates 10 Years

- 06 Jan 2025

In News:

- NITI Aayog, the National Institution for Transforming India, completed its 10th anniversary on January 1, 2025.

- Established to replace the Planning Commission, NITI Aayog was designed to address contemporary challenges such as sustainable development, innovation, and decentralization in a dynamic, market-driven economy.

About NITI Aayog

Establishment and Mandate

- Formation: Created through a Union Cabinet resolution in 2015.

- Primary Mandates:

- Overseeing the adoption and monitoring of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

- Promoting competitive and cooperative federalism between States and Union Territories.

Composition

- Chairperson: Prime Minister of India.

- Governing Council: Includes Chief Ministers (CMs) of all States and UTs, Lt. Governors, the Vice Chairperson, full-time members, and special invitees.

- CEO: Appointed by the PM for a fixed tenure.

Key Achievements

Policy Advisory and Decentralized Governance

- Shifted focus from financial allocation to policy advisory roles.

- Promoted decentralized governance through data-driven initiatives like the SDG India Index and the Composite Water Management Index.

Innovative Initiatives

- Aspirational Blocks Programme (2023): Focused on 500 underdeveloped blocks for 100% coverage of government schemes.

- Atal Innovation Mission (AIM): Trained over 1 crore students through Atal Tinkering Labs and incubation centres.

- Initiatives like e-Mobility, Green Hydrogen, and the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme were conceptualized to drive innovation and sustainability.

Role and Functions of NITI Aayog

Strategic Advice and Federal Cooperation

- Provides policy formulation and strategic advice to both central and state governments.

- Fosters cooperative federalism by encouraging collaboration between the central and state governments.

Monitoring and Evaluation

- Plays a crucial role in monitoring and evaluating policies and programs to ensure alignment with long-term goals.

Promoting Innovation and SDGs

- NITI Aayog contributes to aligning national development programs with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), focusing on innovation, research, and technology in critical sectors.

Key Differences Between Planning Commission and NITI Aayog

Aspect Planning Commission NITI Aayog

Purpose Centralized planning and resource allocation. Focus on cooperative federalism and policy research.

Structure Led by the PM, with Deputy Chairman and full-time members. Led by the PM, with Vice-Chairperson, CEO, and Governing Council.

Approach Top-down, centralized. Bottom-up, encouraging state participation.

Role in Governance Executive authority over policies. Advisory body without enforcement power.

Five-Year Plans Formulated and implemented. Focus on long-term development, no Five-Year Plans.

Challenges Faced by NITI Aayog

- Limited Executive Power: Lacks authority to enforce its recommendations, restricting its influence.

- Coordination Issues: Achieving effective collaboration between central and state governments remains challenging.

- Data Gaps: Inconsistent state-level data hampers accurate policymaking and evaluation.

- Resource Constraints: Limited resources hinder full implementation of initiatives.

- Resistance to Change: Some states resist NITI Aayog's initiatives due to concerns over autonomy and alignment with local needs.

Future Vision and Planning

- Agenda for 2030: Focus on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in areas like poverty alleviation, education, healthcare, clean energy, and gender equality.

- Vision for 2035: NITI Aayog's 15-year vision document aims for sustainable, inclusive growth, with an emphasis on economic growth, social equity, and environmental sustainability.

- Innovation and Digitalization: Promotes digitalization and innovation through data-driven policymaking and regional focus on tribal and hilly areas.

Conclusion: Reflections on the First Decade

- Despite significant achievements, NITI Aayog’s influence remains limited by its advisory role and resource constraints.

- The shift away from centralized planning, evident since the dissolution of the Planning Commission, has sparked debate about the effectiveness of such a model in ensuring long-term development and inclusive growth.

Draft Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025

- 05 Jan 2025

In News:

The Government of India has introduced the long-awaited draft Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025 to operationalize the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. These rules contain several significant provisions, including the controversial reintroduction of data localisation requirements, provisions for children's data protection, and measures to strengthen data fiduciaries' responsibilities.

This development holds substantial implications for both Indian citizens' data privacy and global tech companies, especially with respect to compliance, security measures, and data processing.

Data Localisation Mandates

Key Provision: The draft rules propose that certain types of personal and traffic data must be stored within India. Specifically, "significant data fiduciaries", a category that will include large tech firms such as Meta, Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon, will be restricted from transferring certain data outside India.

- Committee Oversight: A government-appointed committee will define which types of personal data cannot be transferred abroad, based on factors like national security, sovereignty, and public order.

- Localisation Re-entry: This provision brings back data localisation, a contentious issue previously removed from the 2023 Data Protection Act after heavy lobbying by tech companies.

- Impact on Big Tech: Companies like Meta and Google had previously voiced concerns that strict localisation rules could hinder their ability to offer services in India, with Google arguing for narrowly tailored data localisation norms.

Role and Responsibilities of Data Fiduciaries

Key Provision: The rules lay out a clear framework for data fiduciaries, defined as entities that collect and process personal data.

- Significant Data Fiduciaries (SDFs): This subcategory will include entities that process large volumes of sensitive data, such as health and financial data. These companies will be held to higher standards of compliance and security.

- Data Retention: Personal data can only be stored for as long as consent is valid; after which, it must be deleted.

- Security Measures: Data fiduciaries must implement stringent measures such as encryption, access control, unauthorized access monitoring, and data backups.

Parental Consent for Children's Data

Key Provision: The draft rules include provisions aimed at protecting children's data, including mechanisms to ensure verifiable parental consent before children under 18 can use online platforms.

- Verification Process: Platforms must verify the identity of parents or guardians using government-issued identification or digital locker services.

- Exceptions: Health, mental health institutions, educational establishments, and daycare centers will be exempted from needing parental consent.

Data Breach Reporting and Penalties

Key Provision: In the event of a data breach, data fiduciaries are required to notify affected individuals without delay, detailing the breach's nature, potential consequences, and mitigation measures. Failure to comply with breach safeguards can result in penalties.

- Penalties for Non-Compliance: Entities that fail to adequately protect data or prevent breaches could face fines of up to Rs 250 crore.

- Breach Notification: The rules mandate timely reporting of all breaches, whether minor or major, and an emphasis on transparency in the breach notification process.

Safeguards for Government Data Processing

Key Provision: The draft rules seek to ensure that the government and its agencies process citizen data in a lawful manner with adequate safeguards in place.

- Exemptions for National Security and Public Order: The rules also address concerns that the government may process data without adequate checks by stipulating lawful processing and protections when data is used for national security, foreign relations, or public order.

Compliance Challenges for Businesses

Key Challenges: The introduction of these rules will impose several challenges for businesses, particularly tech companies:

- Consent Management: Companies will need to implement robust systems to handle consent records, allowing users to withdraw consent at any time. This will require significant infrastructure changes.

- Data Infrastructure Overhaul: Organizations will need to invest in data collection, storage, and lifecycle management systems to ensure compliance.

- Security Standards: Experts have raised concerns about the vagueness of certain security standards, which could lead to inconsistent implementation across sectors.

Penalties and Enforcement

Key Provisions:

- Penalties for Non-Compliance: Entities failing to adhere to the rules may face significant financial penalties, including fines up to Rs 250 crore for serious breaches.

- Repeat Violations: Consent managers who repeatedly violate rules could have their registration suspended or cancelled.

Conclusion:

The Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025 bring important changes to India’s data privacy framework, particularly the reintroduction of data localisation and more stringent requirements for data fiduciaries. These rules aim to strengthen citizen privacy and ensure greater accountability from businesses. However, the challenges in compliance, especially for global tech firms, and the potential impact on service delivery, will need to be closely monitored as the final rules take shape.

Caste-Based Discrimination in Prisons

- 02 Jan 2025

In News:

The Union Ministry of Home Affairs has recently introduced significant revisions to the Model Prison Manual, 2016, and the Model Prisons and Correctional Services Act, 2023. These changes aim to eliminate caste-based discrimination in Indian prisons and establish a standardized approach to defining and treating habitual offenders across the country.

Background

In October 2024, the Supreme Court of India expressed concerns over the persistence of caste-based discrimination within prisons and the lack of consistency in how habitual offenders are classified. In response, the Court instructed the government to amend prison regulations to promote equality and fairness. The newly introduced reforms are in line with the Court's directives and focus on aligning prison practices with constitutional principles.

Addressing Caste-Based Discrimination in Prisons

The recent amendments take specific steps to combat caste-based discrimination within correctional facilities:

- Ban on Discrimination: Prison authorities are now mandated to ensure there is no caste-based segregation or bias. All work assignments and duties will be distributed impartially among inmates.

- Legal Provision Against Discrimination: A new clause, Section 55(A), titled "Prohibition of Caste-Based Discrimination in Prisons and Correctional Institutions", has been added to the Model Act, establishing a formal legal framework to address caste discrimination.

- Manual Scavenging Ban: The amendments extend the provisions of the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013 to include prisons, prohibiting the degrading practice of manual scavenging or any hazardous cleaning within correctional facilities.

Redefining Habitual Offenders

The updated amendments also standardize the classification and treatment of habitual offenders, in accordance with the Supreme Court’s directions:

- Uniform Definition: A habitual offender is now officially defined as an individual convicted and sentenced to imprisonment for two or more separate offences within a continuous five-year period, provided the sentences were not overturned on appeal or review. Importantly, time spent in jail under sentence is excluded from this five-year period.

- National Consistency: States that do not have specific Habitual Offender Acts must amend their laws within three months to ensure consistency with the new national framework.

Importance of the Reforms

- Promoting Equality: These amendments seek to uphold the constitutional rights of prisoners, ensuring that all individuals, regardless of caste or background, are treated equally and with dignity.

- Eliminating Degrading Practices: The extension of the manual scavenging prohibition to prisons is a vital step in eliminating degrading and inhumane practices, ensuring a more humane environment for prisoners.

- Uniform Framework: The establishment of a standardized definition of habitual offenders ensures a consistent approach in handling repeat offenders across all states, reducing the possibility of arbitrary classifications.

Conclusion

The reforms introduced by the Union Home Ministry mark a significant milestone in India’s prison reform journey. By addressing caste-based discrimination and standardizing the classification of habitual offenders, these amendments reaffirm the country’s commitment to human rights and the rule of law. These changes not only improve the conditions within prisons but also set the stage for future reforms aimed at creating a fairer and more equitable correctional system.

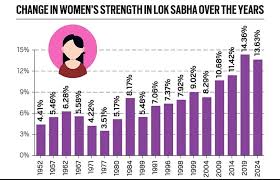

Glass Ceiling Cracks: Women's Rising Role in the 2024 Lok Sabha Elections

- 28 Dec 2024

Introduction:

The 2024 Lok Sabha elections marked a significant step forward for women’s participation in Indian politics. With 800 women candidates contesting across 390 constituencies, this was the highest ever since the 1957 general elections. This surge in women candidates has been a positive reflection of the evolving role of women in India's democratic processes.

Increase in Women Candidates:

- A total of 800 women candidates participated in the 2024 elections, up from 726 in 2019.

- The number of constituencies with no female candidate dropped to a historic low of 152, from 171 in 2019.

- However, despite the rise in participation, only 74 women won, while 629 forfeited their deposits.

Regional Variations:

- The highest number of women candidates were from Maharashtra (111), followed by Uttar Pradesh (80) and Tamil Nadu (77).

- Some constituencies, like Baramati, Secunderabad, and Warangal, saw the highest participation of women, with eight candidates each.

Voter Turnout and Gender Dynamics:

- Women voters surpassed men in voter turnout for the second consecutive time, with 65.78% women casting their vote in 2024, compared to 65.55% of men.

- Assam’s Dhubri recorded the highest female voter turnout at 92.17%, reflecting increased female engagement in the electoral process.

Electoral Data and Gender Insights:

- In 2024, there were 47.63 crore female electors out of 97.97 crore total voters, making up 48.62% of the electorate, a slight increase from 2019.

- The number of female electors per 1,000 male voters reached 946, up from 926 in 2019, showing growing electoral inclusivity.

Challenges and Progress:

- Despite the gains in women’s representation, there remain several constituencies without any female candidates, notably in states like Uttar Pradesh (30 constituencies), Bihar (15), and Gujarat (14).

- Though women's participation has risen, the number of women who win remains disproportionately low, reflecting the challenges they face in a patriarchal political landscape.

Inclusion and Diversity:

- The 2024 elections also saw greater inclusivity, with a rise in third-gender electors, which increased by 23.5% to 48,272.

- Voter turnout among transgender voters nearly doubled, reaching 27.09% compared to 14.64% in 2019.

- Additionally, the number of persons with disabilities (PwD) electors increased to 90.28 lakh, showcasing broader electoral inclusivity.

Conclusion:

The 2024 Lok Sabha elections witnessed a remarkable increase in women’s participation, both as voters and candidates. While the journey toward full gender parity in politics continues, the trends from these elections indicate a growing shift toward more inclusive electoral processes. The data released by the Election Commission further underlines this progress, showing the increasing role of women in shaping India’s democratic future.

Suposhit Gram Panchayat Abhiyan

- 26 Dec 2024

In News:

On December 26, 2024, Prime Minister Narendra Modi presided over the Veer Bal Diwas celebrations at the Bharat Mandap in New Delhi. This annual event commemorates the martyrdom of the sons of Sri Guru Gobind Singh Ji and highlights the importance of nurturing the next generation. During the occasion, PM Modi also launched the ‘Suposhit Gram Panchayat Abhiyan,’ an initiative aimed at improving nutrition and well-being in rural India.

Veer Bal Diwas: Commemorating Sacrifice and Courage

Veer Bal Diwas was declared on January 9, 2022, by PM Modi to honor the sacrifices made by the young sons of Guru Gobind Singh Ji — Sahibzada Baba Zorawar Singh and Baba Fateh Singh — who were martyred in 1704. During the Mughal-Sikh battles, these two brave boys were captured and offered safety if they converted to Islam, which they refused. Their refusal to abandon their faith led to their brutal martyrdom by being bricked alive in the walls of a fort in Sirhind (Punjab). This act of resilience and unwavering faith is a cornerstone of Sikh history and culture.

Veer Bal Diwas not only commemorates their sacrifice but also serves as a reminder of the strength, faith, and courage demonstrated by all four of Guru Gobind Singh Ji’s sons. It underscores the Sikh ideals of sacrifice, courage, and dedication to faith.

Suposhit Gram Panchayat Abhiyan: Addressing Malnutrition in Rural Areas

On the same day, PM Modi launched the 'Suposhit Gram Panchayat Abhiyan', a nationwide mission focused on improving nutritional outcomes in rural areas. The initiative aims to enhance nutrition-related infrastructure and promote active community participation in tackling malnutrition. By encouraging village-level involvement, the program seeks to ensure that nutrition becomes a community-driven effort.

Key Objectives

- Malnutrition Eradication: The initiative focuses on combating malnutrition in rural communities by improving access to better nutrition.

- Healthy Competition: Encourages competition among villages to adopt best practices for nutrition and overall health.

- Sustainable Development: Promotes long-term, sustainable health practices that align with India's broader goals, such as the Poshan Abhiyan and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The program aims to make rural populations active participants in improving their own well-being, strengthening community-driven initiatives for better nutritional outcomes.

Engaging Children and Fostering Patriotism

In line with Veer Bal Diwas, various events were organized to engage young minds across the nation. These initiatives not only raised awareness about the significance of the day but also fostered a culture of courage, dedication, and patriotism.

- Online Competitions: Interactive quizzes were conducted through platforms like MyGov and MyBharat to encourage participation and understanding of Veer Bal Diwas.

- Creative Activities: Schools, Child Care Institutions, and Anganwadi centers organized storytelling, creative writing, and poster-making contests to engage children and promote nationalistic values.

Honoring Young Achievers: PMRBP Awardees

The event also saw the presence of the recipients of the Pradhan Mantri Rashtriya Bal Puraskar (PMRBP), which recognizes children who have demonstrated exceptional abilities in various fields. The awardees, 17 in total, were presented with medals, certificates, and citation booklets by President Droupadi Murmu. These young achievers served as a source of inspiration, reinforcing the theme of celebrating youth potential on Veer Bal Diwas.

Conclusion: Strengthening the Foundation of India’s Future

The celebrations of Veer Bal Diwas and the launch of the Suposhit Gram Panchayat Abhiyan highlight the government’s commitment to nurturing India’s future by investing in its children and rural communities. By honoring historical sacrifices and fostering community-driven health and nutrition initiatives, these efforts contribute to building a resilient, prosperous India that can meet global challenges head-on. The twin focus on children’s development and rural well-being underscores India’s vision of a healthier, more inclusive society, aligned with national and global development goals.

Supreme Court Directs Policy for Sacred Groves Protection

- 20 Dec 2024

In News:

Recently, the Supreme Court of India issued a significant judgment directing the Union Government to formulate a comprehensive policy for the protection and management of sacred groves across the country. These natural spaces, traditionally safeguarded by local communities, play a crucial role in preserving both ecological diversity and cultural heritage.

What are Sacred Groves?

Sacred Groves are patches of virgin forests that are protected by local communities due to their religious and cultural significance. They represent remnants of what were once dominant ecosystems and serve as key habitats for flora and fauna. Typically, sacred groves are not just ecological reserves, but also form an integral part of local traditions, often protected due to spiritual beliefs.

Key Features of Sacred Groves:

- Ecological Value: Sacred groves contribute significantly to biodiversity conservation.

- Cultural Significance: These groves are revered in various religious practices and are central to local traditions.

- Geographical Presence: Sacred groves are found in regions like Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra, and parts of Rajasthan.

Supreme Court's Directive

The court's judgment was based on a plea highlighting the decline of sacred groves in Rajasthan, particularly those being lost due to deforestation and illegal land-use changes. While the Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972 empowers state governments to declare community lands as reserves, the court recognized the need for a unified national policy to protect sacred groves as cultural reserves.

Recommendations:

- Nationwide Survey: The Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEF&CC) was instructed to conduct a nationwide survey to map and assess sacred groves, identifying their size and extent.

- Legal Protection: Sacred groves should be recognized as community reserves and protected under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972.

- State-Specific Measures: The Rajasthan government was specifically directed to carry out detailed mapping (both on-ground and satellite) of sacred groves within the state, ensuring that the groves are recognized for their ecological and cultural significance.

The Role of Sacred Groves in Conservation

Sacred groves play a pivotal role in the conservation of biodiversity. They serve as refuges for various plant and animal species, and the traditional practices associated with these groves, such as tree worship, discourage destructive activities like logging and hunting.

Ecological and Cultural Importance:

- Sacred groves often act as critical biodiversity hotspots, preserving rare and indigenous species.

- They help maintain clean water ecosystems and act as carbon sinks, contributing to climate mitigation.

- Practices of non-interference with these areas have allowed flora and fauna to thrive over centuries.

Cultural Significance Across India

The importance of sacred groves is deeply embedded in India's diverse cultural heritage. They are considered the abode of deities, and various regions have unique names and rituals associated with these groves.

Examples of Sacred Groves in India:

- Himachal Pradesh: Devban

- Karnataka: Devarakadu

- Kerala: Kavu

- Rajasthan: Oran

- Maharashtra: Devrai

Piplantri Village Model

A key example highlighted in the judgment was the Piplantri village in Rajasthan, where the community undertook a remarkable transformation of barren land into flourishing groves. The initiative, driven by local leadership, involves planting 111 trees for every girl child born, which has led to several environmental and social benefits.

Impact of Piplantri's Community Efforts:

- Over 40 lakh trees have been planted, which has recharged the water table by 800-900 feet and lowered the local climate by 3-4°C.

- The initiative has contributed to the reduction of female foeticide and empowered women's self-help groups.

- The village now enjoys economic growth, better education opportunities, and increased local income.

Legal and Statutory Framework

Sacred groves are already recognized under existing Indian laws, notably the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, which allows states to declare sacred groves as community reserves. Additionally, the National Forest Policy of 1988 encourages the involvement of local communities in the conservation of forest areas, a principle supported by the Godavarman Case of 1996.

Key Legal Provisions:

- Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972: Empowers state governments to declare sacred groves as community reserves.

- National Forest Policy, 1988: Encourages community involvement in the conservation and protection of forests, including sacred groves.

- Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006: Suggests empowering traditional communities as custodians of sacred groves.

Looking Ahead: The Need for Action

The Supreme Court has scheduled further hearings to assess the progress of the survey and mapping efforts by Rajasthan. The court also stressed the importance of empowering traditional communities to continue their role as custodians of sacred groves, ensuring their sustainable protection for future generations.

By recognizing the ecological and cultural significance of sacred groves and encouraging community-driven conservation efforts, the Supreme Court’s ruling sets a precedent for more inclusive environmental policies in India. This could also inspire similar initiatives in other parts of the world, promoting the protection of sacred natural spaces for their critical role in maintaining biodiversity and fostering sustainable communities.

Impeachment of Judges

- 12 Dec 2024

In News:

The recent controversy surrounding remarks made by Justice Shekhar Kumar Yadav of the Allahabad High Court has prompted calls for his impeachment. During an event organized by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), Justice Yadav made statements that were perceived as communal, leading to concerns over judicial impartiality. This incident has reignited discussions about the impeachment process for judges in India, highlighting the delicate balance between judicial independence and accountability.

Impeachment Process for Judges in India

In India, the impeachment process for judges, although not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, serves as a mechanism to ensure judicial accountability while safeguarding judicial independence. The process is outlined under Articles 124 and 218 of the Indian Constitution, which govern the removal of Supreme Court and High Court judges, respectively.

Grounds for Impeachment

Judges in India can be removed on two grounds:

- Proved Misbehavior: Conduct that breaches the ethical standards of the judiciary.

- Incapacity: A judge’s inability to perform judicial duties due to physical or mental infirmity.

These grounds are clearly specified to prevent arbitrary removal, ensuring that the process remains fair and just.

Steps in the Impeachment Process

- Initiation of Motion: The process begins when a motion for impeachment is introduced in Parliament, either in the Lok Sabha or Rajya Sabha. The motion must be supported by at least 100 members of the Lok Sabha or 50 members of the Rajya Sabha. This ensures significant parliamentary backing before the motion proceeds.

- Formation of an Inquiry Committee: If the motion is admitted, a three-member inquiry committee is constituted. This includes a Supreme Court judge, the Chief Justice of a High Court, and a distinguished jurist. The committee conducts a thorough investigation into the allegations.

- Committee Report and Parliamentary Debate: Following the investigation, the committee submits its findings. If the judge is found guilty, the report is debated in Parliament. Both Houses must approve the motion by a special majority, which requires a two-thirds majority of members present and voting, as well as a majority of the total membership.

- Final Removal by the President: Once the motion is passed in both Houses, it is presented to the President, who issues the removal order.

Safeguards Against Misuse

The impeachment process includes several safeguards to prevent misuse:

- High Threshold for Initiation: The requirement for significant support from Parliament ensures that the process cannot be initiated frivolously.

- Objective Inquiry: The inquiry committee, comprising legal experts, guarantees an impartial investigation.

- Parliamentary Scrutiny: Both Houses of Parliament are involved, ensuring that the process undergoes democratic scrutiny.

Challenges and Precedents

Despite the rigorous process, no Supreme Court judge has been successfully impeached to date. Past attempts, such as those against Justice V. Ramaswami (1993) and Chief Justice Dipak Misra (2018), were unsuccessful. These instances demonstrate the complexities involved in the impeachment process.

Guidelines for Judges’ Public Statements

Judges in India are entitled to freedom of speech, but they are expected to exercise caution in public statements to maintain the dignity of their office. The Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct (2002) and the Restatement of Values of Judicial Life (1997) outline key principles for judicial conduct, including:

- Non-Interference in Political Matters: Judges should refrain from commenting on political issues to avoid any perception of bias.

- Impartiality: Judges must avoid statements that could prejudice ongoing cases or align them with specific ideologies.

Upholding Judicial Impartiality in a Diverse Society

To maintain impartiality, judges must interpret laws based on constitutional values of justice, equality, and secularism. Furthermore, the judiciary must ensure representation from diverse backgrounds to foster inclusivity and reduce systemic biases. Training programs focused on cultural competence and social diversity are essential to ensure that judges are sensitive to the needs of marginalized communities.

Conclusion

The impeachment process, while stringent, plays a critical role in maintaining judicial accountability in India. As seen in the case of Justice Yadav, judicial conduct, particularly public statements, must be carefully scrutinized to preserve the integrity of the judiciary. Upholding impartiality and adhering to constitutional values are paramount in ensuring that the judiciary continues to function as a neutral arbiter in India’s democracy.

No-Confidence Motion Against Rajya Sabha Chairman

- 10 Dec 2024

In News:

In December 2024, around 60 opposition MPs from the INDIA (Indian National Developmental, Inclusive Alliance) bloc submitted a notice to the Rajya Sabha Secretariat, seeking the removal of Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar from his position as the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha. This unprecedented move has sparked significant political debate, with the opposition accusing Dhankhar of partisanship and bias in the conduct of parliamentary proceedings.

The Charges Against Jagdeep Dhankhar

Allegations of Bias and Partisanship

The opposition has raised several allegations against Dhankhar since his appointment as the Rajya Sabha Chairman in August 2022. These include:

- Partiality towards the ruling government: The opposition claims that Dhankhar has shown bias in favor of the BJP, with accusations of repeatedly denying the Leader of the Opposition, Mallikarjun Kharge, the opportunity to respond to statements made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and BJP President J.P. Nadda.

- Interference in Parliamentary Debates: Opposition MPs have accused Dhankhar of disrupting their speeches and allowing ruling party members to dominate parliamentary discussions.

- Unbecoming Remarks: The notice also refers to comments made by Dhankhar, including praising the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and recalling his association with "so-called cultural organizations." These actions, according to the opposition, violate the non-partisan nature expected of the Chairman.

The Constitutional Framework for Removal of the Vice-President

Legal Provisions for Impeachment

The Vice-President of India, who also serves as the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha, is elected for a five-year term. Article 67 of the Indian Constitution outlines the procedure for his removal:

- Notice Requirement: A motion for the removal of the Vice-President must be introduced in the Rajya Sabha with a prior 14-day notice.

- Approval Process: The resolution must be passed by a majority in the Rajya Sabha and then approved by the Lok Sabha.

- Grounds for Removal: The Vice-President can only be removed through a resolution that is supported by a majority in both Houses of Parliament.

Opposition’s Plan and Challenges

Despite lacking the necessary numbers in the Rajya Sabha to succeed in the impeachment motion, the opposition's move is aimed at sending a political message to the BJP, expressing dissatisfaction with the functioning of the Parliament under Dhankhar’s leadership.

The current session of Parliament is scheduled to end on December 20, 2024, leaving little time for the motion to gain traction. The opposition also does not have the numbers needed for a majority in the Rajya Sabha, which complicates the chances of success for the motion.

Historical Precedents for Similar Resolutions

The last notable attempt to remove a parliamentary officer occurred in 2020 when the opposition moved a no-confidence motion against Rajya Sabha Deputy Chairman Harivansh. This motion was prompted by his decision to extend the session during the contentious farm Bills debate. Although the motion was discussed, it did not result in any significant change.

Similarly, there have been instances where motions to remove Lok Sabha Speakers have been moved but not passed, such as against G.V. Mavalankar in 1951, Sardar Hukam Singh in 1966, and Balram Jakhar in 1987.

Role and Significance of the Vice-President in India

Constitutional Role

The Vice-President of India holds the second-highest constitutional office, primarily functioning as the ex-officio Chairman of the Rajya Sabha. His duties include:

- Presiding over Rajya Sabha Sessions: The Vice-President ensures the smooth functioning of the Rajya Sabha and maintains order during debates. He does not typically vote except in the case of a tie.

- Acting President: In the absence, resignation, or death of the President, the Vice-President assumes the role of the Acting President.

Removal Process Under Article 67

- Article 67(b) of the Constitution specifies the process for the removal of the Vice-President, requiring a 14-day notice and approval from both Houses of Parliament. This provision ensures that any such resolution receives due consideration and is not moved hastily.

Implications for Parliamentary Democracy

- Risks to Parliamentary Integrity: Opposition leaders have expressed concern that the current political environment is eroding the integrity of India’s parliamentary system. They argue that by misusing constitutional offices for partisan ends, the ruling government risks undermining the democratic foundations of the country.

Significance of the Move

- Although the opposition may not succeed in removing Dhankhar, the notice serves as a powerful symbol of resistance. The move underscores the opposition’s commitment to defending the principles of parliamentary democracy and the need for impartiality in the conduct of parliamentary affairs.

Conclusion

The opposition’s push to remove Vice-President Jagdeep Dhankhar from his position as the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha highlights the growing political tensions in India’s Parliament. While the move may not succeed due to the lack of numerical support, it brings to the forefront critical issues regarding the independence of constitutional offices and the functioning of parliamentary democracy in India. The developments around this notice will continue to be a significant point of discussion as the winter session of Parliament draws to a close.

The Controversy around the Sambhal Mosque

- 27 Nov 2024

Introduction

The Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh, has become a flashpoint in a larger religious and legal dispute after a petition was filed questioning its historical origins. Alleging that the mosque was built on the site of an ancient Hindu temple, the case has triggered both legal challenges and violent clashes, raising concerns about communal harmony and the protection of religious sites.

Background of the Dispute

On November 19, 2024, a petition was filed in the Sambhal district court, claiming that the 16th-century Jama Masjid was constructed over the site of an ancient Hari Har Mandir. This claim mirrors similar petitions filed in other parts of India, including Varanasi, Mathura, and Dhar, where Hindu groups have sought to alter the religious character of mosques they believe were built on temple sites. The petitioners in the Sambhal case include advocate Hari Shanker Jain, a key figure in the Gyanvapi and Mathura disputes.

Survey and Clashes

The Sambhal court ordered a survey of the mosque on November 19, 2024, to investigate the historical claims. The initial phase of the survey, conducted peacefully, involved mosque authorities and local police. However, a second survey on November 24 escalated tensions, as it was accompanied by a procession led by a local priest chanting Hindu slogans. Protests soon turned violent, leading to stone-pelting, police firing, and at least five deaths, including two teenagers. Locals accused the police of excessive force, while the police denied allegations of shooting.

The Mosque’s Historical Context

The Shahi Jama Masjid was built by Mughal Emperor Babur's general, Mir Hindu Beg, around 1528. It is one of the three mosques constructed during Babur's reign, the other two being in Panipat and Ayodhya. Architectural studies suggest it was constructed using stone masonry with plaster, and while some historians believe it was built on a pre-existing structure, the mosque’s historical context is complex. Local Hindu tradition holds that the site was originally a Vishnu temple, with the belief that Kalki, the tenth avatar of Vishnu, will arrive there.

Legal Implications: The Places of Worship Act, 1991

The dispute touches upon the Places of Worship Act, 1991, which mandates the preservation of the religious character of all places of worship as they existed on August 15, 1947. The Act was designed to prevent further disputes over religious sites, except for the Babri Masjid case, which was already under litigation at the time. The petitioners in the Sambhal case argue that the religious character of the mosque should be altered, contradicting the Act’s provisions.

Challenges to the Places of Worship Act

The Places of Worship Act has been criticized for barring judicial review and preventing any changes to the religious status of sites that existed before India’s independence. Some legal experts suggest that while an inquiry into the religious nature of a place might be permissible, changing that character would violate the Act. The ongoing legal challenges in the Supreme Court, including cases from Varanasi, Mathura, and now Sambhal, highlight the complexities of reconciling India’s legal framework with communal sensitivities.

Conclusion

The Sambhal mosque dispute underscores the challenges in balancing India’s legal framework with religious and communal dynamics. While the Places of Worship Act aims to preserve the status quo, petitions challenging it have revived contentious debates over historical monuments and their religious significance. As the legal proceedings continue, the case will likely have far-reaching implications for India’s secular fabric and the preservation of communal harmony.

Challenges in Municipal Financing

- 25 Nov 2024

Introduction

Municipal corporations (MCs) in India are essential service providers in urban areas, but they face severe financial constraints, which hinder their ability to provide quality services. While urban India contributes almost 60% of the nation's economic output, MCs are heavily reliant on state and central government transfers, limiting their financial autonomy and operational capacity.

Key Issues in Municipal Financing

- Limited Revenue Generation

- Low Property Tax Revenues: Property tax, the main source of municipal revenue, contributes only 0.12% of GDP, a figure that reflects poor tax collection mechanisms and outdated property valuation systems.

- Revenue Concentration: Over 58% of municipal revenue comes from the top 10 cities, highlighting fiscal disparity between urban areas.

- Dependence on Government Transfers: Municipalities rely significantly on state and central transfers, constituting a large portion of their revenue. This reduces their ability to plan and execute long-term projects independently.

- Inefficiency in Tax and Fee Collection

- Ineffective Property Tax Systems: Existing tax formulas do not reflect actual property valuations, leading to under-taxation and revenue loss.

- Inadequate User Charges: Fees for essential services like water supply, sanitation, and waste management are not regularly adjusted, impacting cost recovery and service quality.

Strategies for Strengthening Urban Local Bodies (ULBs)

- Enhancing Revenue Sources

- Property Tax Reforms: Implementing GIS-based property tax mapping and linking tax rates to actual property valuations can improve tax compliance and revenue generation.

- Rationalising User Charges: Regular adjustments to service fees for water, sanitation, and waste management can ensure cost recovery and better service delivery.

- Reducing Dependence on Transfers

- State and Central Transfers: A rule-based framework for government transfers, accounting for inflation and city growth, can ensure predictability and adequate compensation for MCs.

- Boosting Non-Tax Revenues: MCs can increase income from user fees (e.g., for urban transport and waste management) and explore public-private partnerships (PPPs) to enhance service delivery.

- Leveraging Technology for Efficiency

- Digitalisation and Automation: Streamlining processes through technology can reduce inefficiencies, cut down on waste, and free up resources for capital expenditure.

- Monitoring Systems: Improved monitoring and reporting can reduce pilferage, enhance revenue collection, and ensure accountability.

Fiscal Management and Innovative Financing

- Municipal Bonds and Innovative Financing

- Larger MCs are already using municipal bonds to fund infrastructure projects. Smaller cities can adopt similar financing instruments to diversify funding sources and attract private investment.

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Fostering partnerships in sectors like urban transport and waste management can attract private investment and reduce the financial burden on MCs.

- Resource Pooling for Infrastructure Projects

- MCs can collaborate to pool resources for large-scale projects, such as renewable energy or urban transport initiatives, overcoming fiscal constraints that individual corporations face.

Government Initiatives for Urban Governance

- Citizen-Centric Programs

- Swachh Sarvekshan (2017) promotes citizen participation to improve urban cleanliness.

- Swachh Bharat Idea Book empowers citizens to propose innovative solutions to urban challenges.

- Performance-Based Indices

- Ease of Living Index (2017) and the Municipal Performance Index (2019) assess urban quality of life, service delivery, and governance, encouraging better performance in ULBs.

Conclusion

Empowering urban local bodies is crucial for effective urban governance and development. By improving revenue generation through reforms, reducing dependence on transfers, and adopting innovative financing mechanisms, municipal corporations can enhance their capacity to meet the growing demands of urbanization. Collaborative efforts between the government, civil society, and academia are essential to ensure sustainable urban development and better living conditions for urban residents.

The Fight for Accessibility and Dignity in Indian Prisons

- 24 Nov 2024

Introduction

Prisons in India face numerous systemic issues, with overcrowding, abuse, and neglect being prevalent. For prisoners with disabilities, these challenges are magnified, as they struggle with basic needs and lack necessary accommodations. This issue is not only a human rights violation but also a failure in the implementation of legal protections.

Prison Conditions and Accessibility Issues for Disabled Inmates

- Challenges Faced by Disabled Prisoners: Disabled prisoners, such as Professor G.N. Saibaba, who spent a decade in prison before being exonerated, face severe challenges in performing everyday tasks like using toilets or taking baths. His experience of being physically lifted by fellow inmates due to the lack of wheelchair accessibility highlights the systemic neglect.

- Exclusion and Abuse: Prisoners with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to abuse, as their specific needs are ignored. The government does not track the number or conditions of disabled prisoners, which leads to neglect and mistreatment. Notably, Father Stan Swamy, who had Parkinson's disease, was denied essential items like a straw, affecting his ability to eat and drink.

Legal Framework and International Obligations

- Constitutional Protections: The Indian Constitution guarantees rights to prisoners, including protection from torture (Article 21) and the right to fair legal processes (Article 22). The Supreme Court has reinforced the need for humane treatment in prisons through various judgments.

- International Commitments: India has committed to international conventions such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Nelson Mandela Rules, which require reasonable accommodations for disabled prisoners. Despite these commitments, the practical enforcement of such rights remains minimal.

- Domestic Legislation: The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, mandates the protection of disabled individuals from abuse and exploitation. However, violations like the denial of basic assistive devices to prisoners show a gap in enforcement. The Ministry of Home Affairs has issued guidelines for prison accessibility, but they have yet to be widely implemented.

Systemic Failures and Lack of Political Will

- Overcrowding and Inadequate Infrastructure: Indian prisons house over 5.73 lakh prisoners, far exceeding their capacity. This overcrowding exacerbates the challenges faced by disabled prisoners, as the infrastructure is inadequate to meet their needs. A 2018 audit of Delhi’s prisons revealed significant accessibility gaps, such as inaccessible cells and toilets, making daily life for disabled prisoners even more difficult.

- Political Apathy and Public Indifference: Many believe that prisoners deserve their suffering, fueling a lack of urgency in addressing prison reforms. However, the state is responsible for ensuring the rights and dignity of all prisoners, including those with disabilities. There is a need for a shift in societal attitudes to ensure that these rights are upheld.

Reforms and the Way Forward

- Infrastructure and Accessibility: Prisons must implement universal design principles, ensuring that infrastructures are accessible to all, especially prisoners with disabilities. This includes accessible cells, toilets, and common areas, as well as functional wheelchairs.

- Judicial and Legal Reforms: The judicial system must expedite trials, especially for undertrials, and ensure that all prisoners have access to legal representation. This would help alleviate the overcrowding crisis and improve the overall functioning of the prison system.

- Comprehensive Rehabilitation and Welfare Programs: Prison systems need to focus on rehabilitation rather than mere punishment. Programs for skill development, education, and mental health support should be integrated into prison routines, providing prisoners with opportunities for personal growth and reintegration into society.

- Strengthening Oversight Mechanisms: There must be greater transparency in prison management through independent oversight bodies and regular audits. A whistleblower mechanism can help report violations of prisoner rights, ensuring greater accountability.

Reimagining Governance with AI: The Promise of GovAI

- 20 Nov 2024

In News:

India's rapid digital transformation, coupled with the advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI), presents a unique opportunity to reimagine governance. The concept of GovAI—using AI to enhance public administration—holds the potential to revolutionize governance, improve efficiency, and create more responsive and inclusive public systems.

Digital Transformation in Governance

- Evolution of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI)

- Over the past decade, India has made significant strides in digital governance through the development of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI). DPI has reduced inefficiencies, enhanced transparency, and improved service delivery, transforming India's governance landscape.

- Impact of AI on Governance

- As AI becomes a critical enabler in various sectors, its application to governance promises to deliver more efficient, inclusive, and responsive government services. The potential of AI lies in its ability to provide more with less, driving innovation across key public services.

Key Trends Driving GovAI

- Rapid Digitalization of India

- Currently, 90 crore Indians are connected to the Internet, with projections indicating 120 crore by 2026, positioning India as the most connected country globally.

- Digitalization serves as the backbone for AI-driven governance, enabling efficient data collection, analysis, and informed policy-making.

- Data as a Valuable Resource

- The rapid digitalization of India has led to the generation of vast amounts of data. This data serves as the fuel for AI models, which can be used to enhance governance.

- Programs like the IndiaDatasetsProgramme aim to harness government datasets for AI development while safeguarding data privacy through legislation.

- Demand for Efficient Governance

- The post-COVID world has underscored the need for governments to deliver better outcomes with fewer resources. AI has the potential to optimize the use of public resources, enabling more efficient and targeted governance.

India’s Leadership in AI-Driven Governance

- Positioning India as a Global Leader

- India’s digital governance initiatives have placed it at the forefront of AI adoption in the public sector. Through GovAI, India can solidify its position as a global leader in using technology for public good.

- As the Chair of the Global Partnership on AI (GPAI), India is advocating for the inclusive development of AI to ensure that it benefits all nations, not just a select few.

- Role of Innovation Ecosystem

- India’s innovation ecosystem, comprising startups, entrepreneurs, and tech hubs, can play a crucial role in driving the development of AI models, platforms, and apps for governance.

- A strong partnership between the government and private sector is essential to successfully deploy AI solutions across various sectors of governance.

Potential Benefits of GovAI

- Enhanced Efficiency and Service Delivery

- AI-powered tools, such as chatbots, can provide citizens with 24/7 assistance, streamlining public service delivery and reducing waiting times.

- AI can help in automating processes and improving the overall efficiency of government operations.

- Data-Driven Decision-Making

- AI can analyze large datasets to make informed policy decisions and design targeted interventions in sectors like healthcare, education, and social welfare.

- Data-driven insights can enhance the effectiveness of welfare schemes, improving outcomes for marginalized communities.

- Increased Transparency and Accountability

- AI can enhance transparency in governance by minimizing human intervention in processes, thus reducing corruption and ensuring efficient use of public resources.

- Predictive analytics and real-time data monitoring can enable proactive governance, preventing issues before they escalate.

Challenges and Drawbacks of GovAI

- Privacy Concerns

- The use of AI in governance requires the collection and analysis of vast amounts of personal data, raising concerns about data privacy and surveillance.

- Robust data protection laws must be enforced to ensure citizens' data is handled responsibly.

- Accountability and Bias

- AI systems may produce biased outcomes depending on the data they are trained on. Ensuring accountability for decisions made by AI systems remains a challenge, particularly when errors or biases occur.

- Transparent mechanisms must be established to hold AI systems accountable for their actions.

- Increased State Control and Surveillance

- The integration of AI in governance could lead to increased state control, potentially compromising individual freedoms. Ensuring that AI is used responsibly to balance power between the government and citizens is critical.

- Digital Divide

- The benefits of AI in governance may not be evenly distributed across the population, exacerbating the digital divide.

- Efforts must be made to ensure that marginalized communities, without access to digital technologies or skills, are not left behind.

Conclusion

- Balancing Benefits and Risks

- The integration of AI into governance systems presents significant benefits, including enhanced efficiency, transparency, and proactive governance. However, there are challenges related to privacy, accountability, and state control.

- To ensure AI serves the public good, India must implement strong regulatory frameworks, promote transparency, and develop ethical AI systems that respect citizens’ rights and freedoms.

- Moving Toward Maximum Governance

- AI can help realize the vision of maximum governance, enabling more effective and targeted interventions across sectors like healthcare, security, education, and disaster management.

- The success of GovAI will depend on a trusted partnership between the government, private sector, and innovation ecosystem, ensuring that AI technology serves the larger public interest.

Khap Panchayats: Evolving Towards Modern Governance and Justice

- 17 Nov 2024

Why in the News?

Khap Panchayats have attracted attention due to their evolving role in addressing key socio-economic issues like unemployment, education, and rural development. Modernization efforts are underway to regulate these traditional councils, integrating them into formal Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) systems for better governance, accountability, and social justice.

What are Khap Panchayats?

Definition and Origin:

Khap Panchayats are community-based councils primarily found in North India, particularly in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and parts of Rajasthan. These informal bodies, composed of elders from kinship groups (Khaps), have historically served as local governance bodies that resolve disputes within their communities. Their origins trace back centuries and they function alongside formal legal systems, often prioritizing customary norms over constitutional law.

Historical Role:

Historically, Khap Panchayats have maintained social order in rural areas, acting as forums for dispute resolution related to marriage, property, and community matters. While their decisions were respected within their communities, they operated parallel to formal courts, and their influence was often seen as a stabilizing force in rural society. However, their structure has also contributed to the perpetuation of patriarchal practices and social exclusion.

Issues with Khap Panchayats

- Patriarchal Practices:Khap Panchayats have often been associated with gender inequality. They enforce rigid social norms that limit women's autonomy, particularly in matrimonial matters, inheritance rights, and personal freedoms. This has led to criticism for their role in suppressing women's rights.

- Honor Killings and Social Conservatism:Khap Panchayats are notorious for opposing inter-caste and same-gotra marriages, at times even endorsing honor killings to preserve social order. Such practices are violations of fundamental rights and personal freedoms guaranteed by the Indian Constitution.

- Legality Concerns:The decisions of Khap Panchayats often clash with constitutional values such as equality, personal liberty, and dignity. Their informal judgments lack legal validity and frequently violate the rule of law, raising significant concerns about their adherence to India’s legal framework.

- Caste-based Discrimination:Khap Panchayats have been criticized for reinforcing caste hierarchies, which leads to discrimination and exclusion of marginalized communities. Their focus on preserving traditional caste structures often results in the oppression of the vulnerable, particularly lower-caste groups.

Gender Dynamics and Evolving Roles of Khap Panchayats

In recent years, some Khap Panchayats have started to show more progressive and inclusive stances, particularly in promoting gender justice:

- Support for Women Athletes:Khap Panchayats have begun to recognize and celebrate the achievements of women, particularly in sports. Several Khap bodies have felicitated women sportspersons, contributing to a growing culture of sports among rural women. This marks a shift from their traditionally patriarchal stance.

- Promoting Gender Justice:Notably, the MehamChaubisiKhap in Haryana has played a significant role in advocating for women’s rights and gender equality. It was involved in supporting the 2023 wrestlers' protest against sexual harassment, demonstrating a shift towards gender-related activism and social reform.

Supreme Court Ruling on Khap Panchayats:

In the landmark Shakti Vahini v. Union of India case (2018), the Supreme Court of India addressed the issue of honor killings and inter-caste marriages. The Court emphasized that honor killings violate fundamental rights and called for strict measures to prevent such crimes. The Court further directed state governments to establish special protection cells for couples facing threats from their families and communities. This ruling underscored the importance of personal liberty and freedom of choice, regardless of community or caste.

What is Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)?

Definition and Importance:

Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) refers to methods of resolving disputes without resorting to formal litigation. These methods include mediation, arbitration, and conciliation, all of which encourage cooperative problem-solving and mutually agreeable solutions. ADR is particularly important in India due to the overburdened judicial system, which faces a backlog of cases and delays.

ADR offers several advantages, including:

- Cost-effectiveness

- Confidentiality

- Flexibility

- Improved relationships between parties involved

Types of ADR Mechanisms:

- Arbitration: A formal process where an arbitrator resolves disputes and their decision is legally binding.

- Conciliation: A third-party neutral assists the parties in reaching an agreement, and the recommendations can be accepted or rejected.

- Mediation: A mediator facilitates communication between disputing parties, helping them reach a voluntary and mutually agreeable resolution.

- Negotiation: A direct negotiation between the parties without third-party involvement, aiming for a mutually acceptable settlement.

Integrating Khap Panchayats into the Formal ADR System

Given the potential of Khap Panchayats as community-based governance bodies, integrating them into the formal ADR framework can significantly enhance their role in dispute resolution. Here are some strategies for modernizing Khap Panchayats:

- Legal Recognition of ADR Role:Khap Panchayats can be legally recognized within the ADR framework, formalizing their role in mediation and dispute resolution, ensuring their decisions align with constitutional norms and human rights.

- Training and Capacity Building:Khap leaders can undergo training in ADR techniques such as mediation and arbitration, equipping them with skills to resolve conflicts impartially and in line with legal standards. This would help transition Khaps from informal bodies to more structured and legally compliant dispute resolution mechanisms.

- Legal Regulation and Oversight:Regulations can be put in place to define the scope and limitations of Khap Panchayats' authority, ensuring their decisions do not violate human rights or the constitution. Oversight mechanisms should be established to monitor their actions and prevent practices like honor killings or forced marriages.

- Shift Towards Developmental Roles:Some Khap Panchayats are already advocating for progressive reforms in areas like unemployment, education, and rural development. By focusing on these issues, Khap Panchayats can serve as agents of social change and contribute to community development.

- Awareness and Accountability:Awareness campaigns can educate rural communities about constitutional rights and the legal system, emphasizing the importance of formal legal frameworks and human rights. At the same time, Khap Panchayats should be held accountable for actions that undermine justice or equality.

- Collaboration with Formal Institutions:Khap Panchayats can collaborate with local governance bodies and judicial institutions, ensuring that their decisions align with the rule of law and contribute to social justice. This would enhance their role in inclusive decision-making and legally sound governance.

Conclusion

Khap Panchayats, with their deep-rooted history and influence, have the potential to evolve into modern governance institutions. By integrating them into the formal ADR framework, aligning their practices with constitutional values, and focusing on community development, they can contribute positively to dispute resolution and social reform in rural India. This transformation will require legal regulation, training, oversight, and awareness to ensure that Khap Panchayats function as effective, equitable bodies that respect the fundamental rights of all individuals.

Net Borrowing Ceiling

- 16 Nov 2024

In News:

- In 2023, the central government imposed a Net Borrowing Ceiling (NBC) on Kerala, limiting its borrowing capacity to 3% of the projected Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) for the fiscal year 2023-24.

- Impact on Kerala’s Finances: This ceiling has significantly impacted Kerala’s ability to meet its expenditure needs and fund developmental activities, triggering political and legal disputes. Kerala has approached the Supreme Court of India, arguing that the imposition of NBC infringes upon its constitutional rights under Article 293 of the Indian Constitution.

Constitutional Provisions on Borrowing Powers

Article 292: Borrowing Powers of the Centre

- Central Government’s Borrowing: Article 292 grants the Central Government the authority to borrow money on the security of the Consolidated Fund of India.

- Limits on Borrowing: The extent of borrowing by the Centre is determined by laws enacted by Parliament.

Article 293: Borrowing Powers of the States

- State Borrowing: Article 293 allows State Governments to borrow within India against the Consolidated Fund of the State. However, it imposes certain conditions:

- If a State has outstanding loans or guarantees given by the Centre, the Centre’s consent is required to raise further loans.

- The Central government can impose conditions when granting such consent.

Centre’s Role in State Borrowing

- Article 293(3) allows the Centre to impose conditions on a state’s borrowing if it has existing liabilities or guarantees outstanding.

- The Centre has wide discretion in granting or denying consent, which has been a point of contention in Kerala’s case.

The Imposition of Net Borrowing Ceiling (NBC)

Scope of the NBC